The Price of Eating Green

A choice that is simply too costly for many people

Walking down the aisles of Newport Market, the words “organic” and “sustainably produced” jumped out from nearly every box, can and bag on the shelf, as did the prices. Was it worth it, I asked? The Earth-loving, all-organic, carbon-conscious part of myself said yes. Yet how could someone less privileged come to the same conclusion? Making healthy decisions for both ourselves and the planet is simply a luxury many in our community can’t afford.

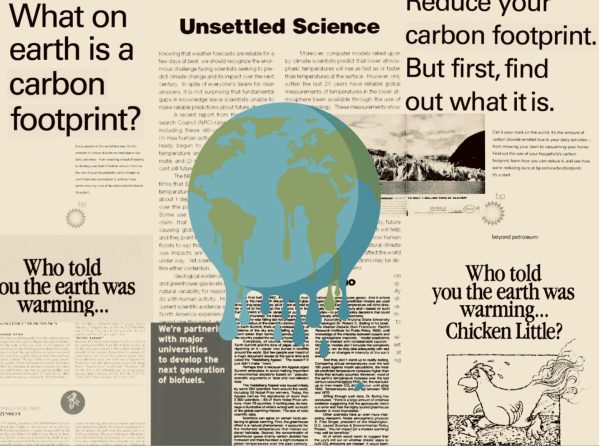

A recent push for greener lifestyles has led to many positive changes, but it has also enabled companies to take advantage of the new “trend.” Ultimately, sustainability must become financially possible in order for communities to achieve a true state of “green.” Much like incentives offered for electric cars and solar panels, people must be encouraged, not discouraged, to eat in environmentally-friendly ways.

For starters, organic products are more expensive than their less environmentally friendly counterparts. According to BlueWeave Consulting and Daily Business News, the organic food market is predicted to grow 8.7% annually, compared to 3.8% for the entire food industry. Additionally, a U.S. Department of Agriculture investigation reports the price difference, or “premium,” between organic and non-organic foods, such as 82% for eggs, 72% for milk, 60% for salad mix, 54% for canned beans, 53% for spaghetti sauce and 44% for celery. Even items like baby food, potatoes and bread have a significant premium.

Julie Zwillich is a mother of two—both of her children currently attend Summit High School.

“I was much more strict about [buying organic] when my kids were babies… because I remember reading that children in fast developmental stages might be more susceptible to chemical (pesticide) interference,” explained Zwillich. “But as they’ve gotten older… I am less apt to pay organic prices when they seem unfairly high.” Like many others, Zwillich questions what “organic” really means and “sometimes [wonders] if we’re all getting ripped off”.

In some cases, the difference in price is to be expected. For example, the prohibited use of pesticides and hormones (for organic products) leads to a smaller yield, and therefore a greater cost needed to maintain operations. Smaller-scale businesses also cost more money to operate compared to their overall profit. Factor in sustainable energy, recyclable packaging and eco-certifications/inspections mean many of these prices are justified. At the same time, there are other companies that use this movement for their own benefit.

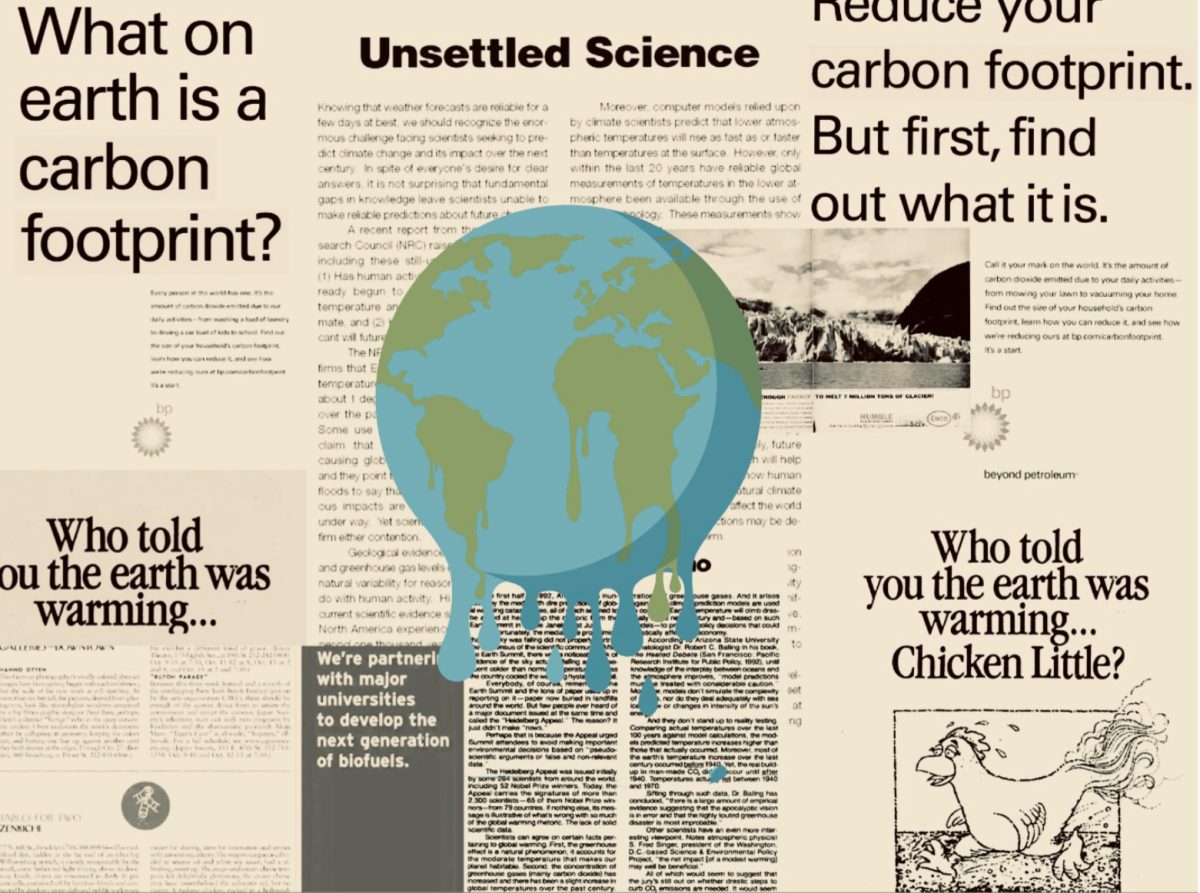

“Greenwashing,” a term coined by environmentalist Jay Westerveld, describes deceptive tactics used by businesses to advertise a product as being environmentally friendly. Sometimes, claims about sustainability are not provable, irrelevant or vague. In other cases, a company advertises one way that they’re green, although they may fall short in all other categories. Bait and switch, creating one line of environmentally friendly products to hook buyers, is another common strategy. Product packaging and labels can also include pictures that are associated with positive qualities, such as images of a family with a cow or a man harvesting fruit by hand. To emphasize the severity of this problem, a report from the European Commission found that 42% of environmentally-friendly claims (found online) were false, exaggerated or misleading.

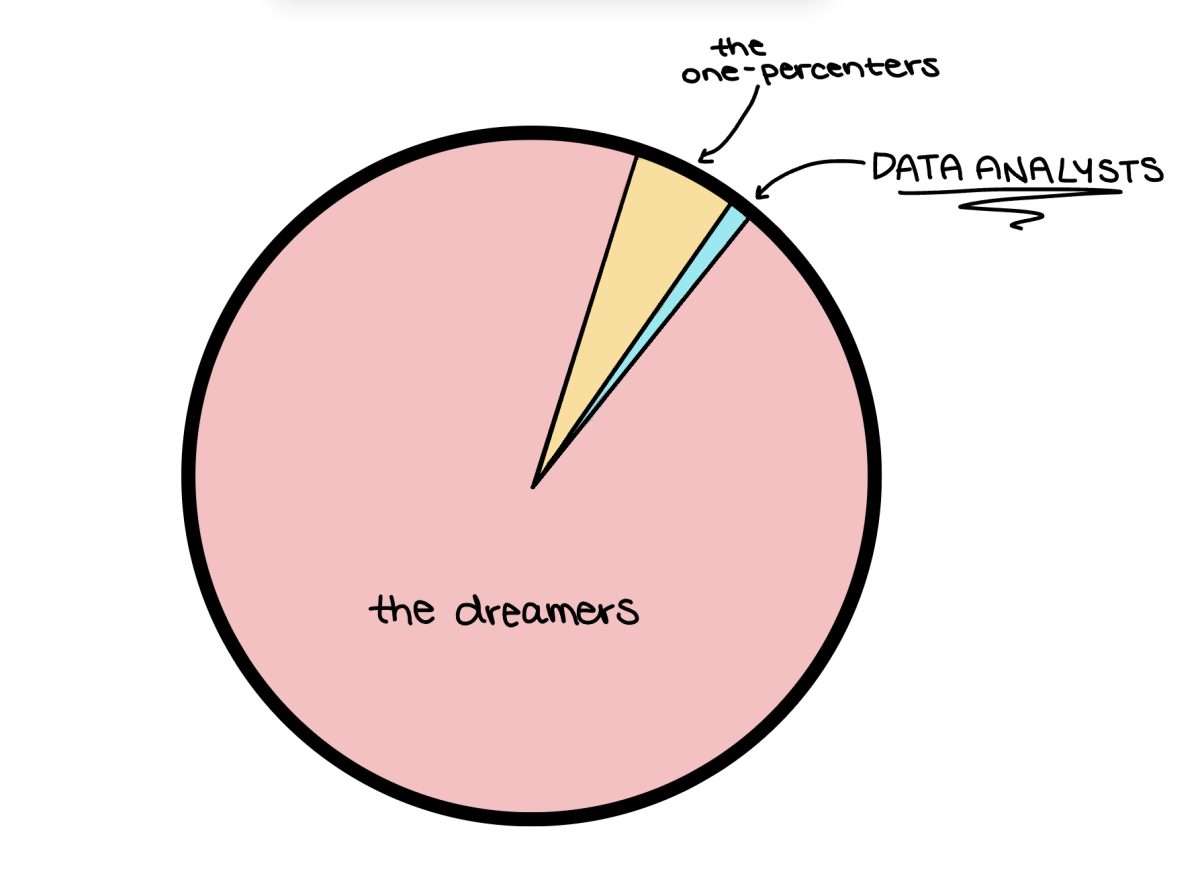

Despite greenwashing, many continue to invest in healthy eating. It’s no coincidence that restaurants like Active Culture and Mother’s Cafe are always packed. Eating healthy is an ongoing fad (one of the main reasons that the market for green food has expanded). For instance, actress Gwenyth Paltrow decided to accept a challenge posed by the Food Bank for New York City: spend only $29 per week (the amount given to some families by the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) on food. With her allotted money, Paltrow bought black beans, whole grain brown rice, seven limes, an avocado, a tomato, multiple heads of lettuce and cilantro (among a few other things) and posted a picture online. The esteemed actress quit the challenge after four days.

Although most families would have more than $29 available, Paltrow’s post received backlash because many households, much less economically-burdened ones, wouldn’t waste money on foods like the ones she purchased. Instead, someone could get more for the same price if they purchased inexpensive (usually processed) foods. A Feeding America study found that 78.7 percent of the households that they surveyed buy inexpensive, unhealthy food in order to make their resources last longer. This contributes to higher rates of obesity among lower-income people.

“[I]t’s almost always more expensive. Sometimes much more. It is definitely discouraging and has me constantly thinking about accessibility and fairness in our society,” Zwillich said.

As a more “privileged” school, many students at Summit might not realize how these issues are currently affecting people in Central Oregon. But according to the latest census, 10% of Bend’s population lives in poverty (defined as a family income lower than the threshold for that household). While only 13.03% of the people at Summit were eligible for free and reduced lunch in 2021, that same number was 35.47% at Bend High School and 75.57% at LaPine Middle School. A shocking 94.50% of those at M.A. Lynch Elementary in Redmond were eligible two years ago.

Services such as free and reduced lunches are undeniably important to many members of our community. These programs aim to provide participants with nutritious, healthy meals. But public institutions, including schools, don’t have the funding to buy costly organic and sustainably produced foods. Inequities around eating and environmentally friendly lifestyles continue to persist despite some steps in the right direction.

Even at home (and in less extreme situations), many struggle with maintaining a diet that is beneficial for their bodies and the planet. Avery Suriano, a junior at Summit High School, was vegan up until recently. She describes how she couldn’t eat what the rest of her family did and had to buy some of her own food.

“[Even] fresh, decent, high-quality produce [was] expensive,” said Suriano. Combined with the price of vegan alternatives, the cost adds another layer of complexity to some diets. “[The price] wasn’t something that made me not be vegan anymore, but it was definitely something that I was like, ‘Oh, I don’t have to deal with this anymore,’” describes the junior. “When I wasn’t vegan, it was kind of like a weight was lifted.”

Eating green is the right choice for the planet and our bodies, but there is a price that one must pay in order to do their part. Moving forward, healthy eating shouldn’t be a luxury, a trend or a marketing tactic – it should be a habit, something that we don’t even think about. Only then will sustainability and a future for Earth be achievable.

Usually found outside, the wild Dailey can be spotted frolicking in the woods or on top of a mountain. She enjoys visiting unknown places whether that’s traveling to Myanmar or backpacking into the middle-of-nowhere...