It’s nearly June, and we are headed towards (optimistically speaking) the season where we decide which novels are worth spending valuable summer reading time on. It’s easy to stay in your comfort zone as a reader, perusing novels from similar genres and authors that you can safely guess you’ll enjoy based on past reading. However, that leaves a great deal of content unexplored. Reading is one of the best ways to expand your worldly perspective, and a great first step in doing so is venturing into international novels.

Japanese literature comes highly recommended and offers a unique perspective, most importantly because of the difference in communication style between Japan and America. Because Japan has such a culture in which contextual clues such as body language and tone have a significant impact on the way messages are interpreted, Japanese authors often leave much unsaid. This forces the Western reader to think about literature in a different way, fundamentally changing the way we understand these novels. If you’re in search of recommendations, look no further—here are three Japanese novels I’ve personally enjoyed this year. Here are three Japanese novels I’ve read this year and can confirm made me think.

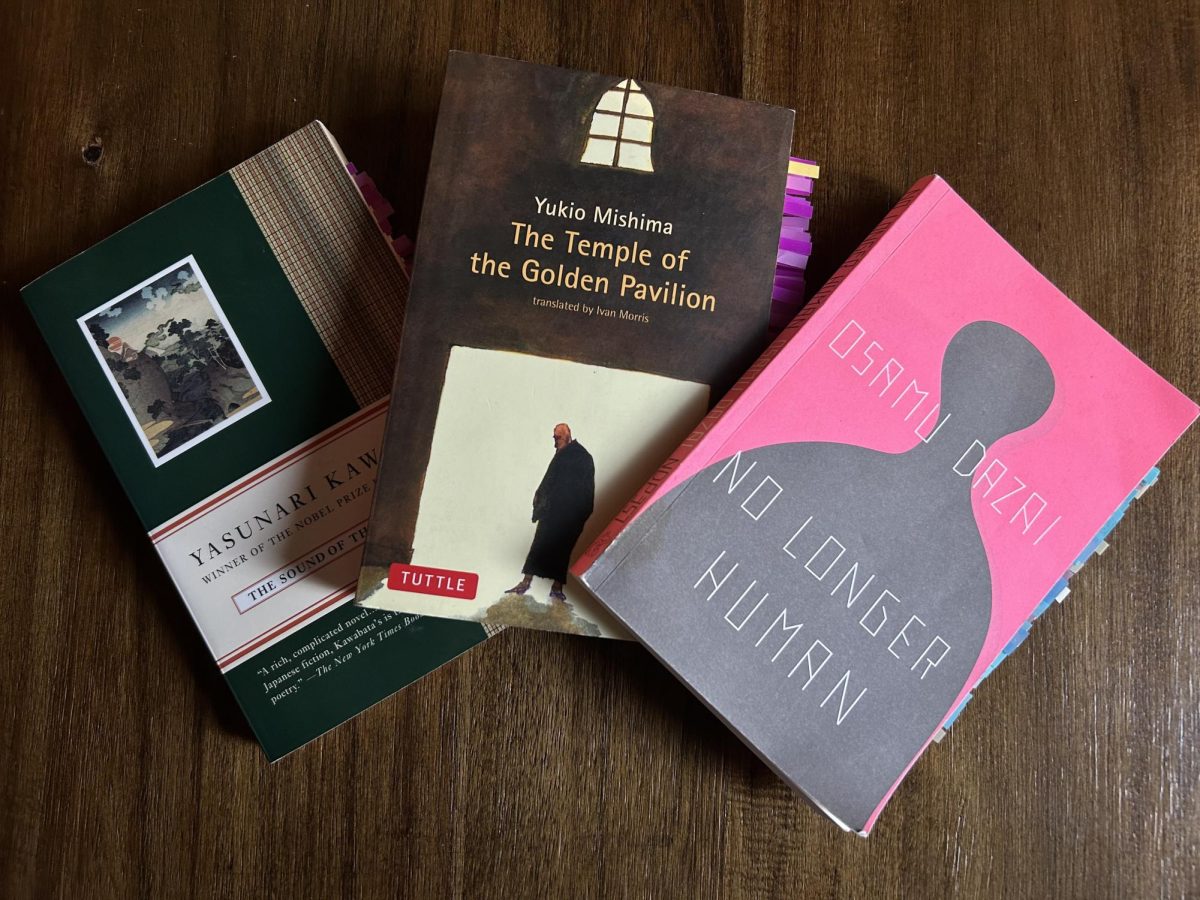

The Sound of the Mountain by Yasunari Kawabata

“The Sound of the Mountain” presents the story of Ogata Shingo, an aging man with recurring memory issues, as he grapples with the reality of his mortality and the legacy he’ll leave behind. The author of this novel, Yasunari Kawabata, was the first Japanese author to win the Nobel Prize in literature. He received the award in 1968 after the publication of this novel and is lauded for his subtle and descriptive style. Like many of his other novels, “The Sound of the Mountain” is a heavily character-driven story, with much of the major events happening in summary in favor of longer, more descriptive scenes focused on dialogue and the narrator’s thought process. Shingo’s experience centers on coming to terms with his impending death as he grapples with the mistakes of his past and how they will impact his legacy as well as his children. He’s highly superstitious, seeing deep significance in small changes in nature, his dreams, and seeming coincidences he observes. He’s also extremely attentive, reading into what others will not say, and treads lightly when attempting to maintain the traditional family structure he strives for—a clear demonstration of the Japanese cultural difference in communication. Shingo attempts to approach the world with a grounded common sense, maneuvering as to not cause drama or upset the balance too much while protecting the integrity of his family. He feels a strong sense of responsibility for mistakes made in his life that hurt his children, perceiving that his failings as a parent caused the eventual tragedies that afflict his son and daughter. He takes measures to fix these problems, or at least help out in a traditional way, but throughout the novel Shingo’s powerlessness to stitch up his children’s wrongdoings becomes increasingly evident. All of his struggles to maintain the balance and harmony of his family only leave him exhausted. Kawabata flawlessly portrays the character’s thought process as he comes to terms with his situation and reflects on his past, making this novel one you’ll return to again and again.

The Temple of the Golden Pavilion by Yukio Mishima

“The Temple of the Golden Pavilion” narrates the sequence of events that led a young man to purposefully burn down the temple in which he resided as a Buddhist acolyte, a story based on a real event in 1950. The novel follows a character who is as compelling as his author. In many places, it’s clear to see where fragments of Mishima bleed into the protagonist of his most popular novel, Mizoguchi. A pattern for this author is writing characters who are tormented by extreme psychological problems and spiral into an obsession over unattainable ideals that they cannot experience happiness without, and Mizoguchi is no exception. His story is told in compelling, descriptive detail that one would expect from a protégé of the previously mentioned Yasunari Kawabata. The mode of Mishima’s death was ritual suicide by disembowelment (termed seppuku) in front of a military building in Tokyo after delivering a speech about overthrowing the Japanese government and rearming the military—he was then decapitated by one of his eighty followers in an army he’d built to support the traditional Japanese martial spirit. Something about the world was clearly sitting very wrong for him, and this dissatisfaction (to put it mildly) shows up strongly in Mizoguchi’s character. Mizoguchi is an alienated, aesthetically oriented person haunted by his inability to communicate and fit in with others due to a stutter. He grows to see the world as increasingly dark and evil, which he attempts to reconcile himself with by embracing evil within himself and deciding that the way to escape loneliness is by hurting others. The Temple taunts him as a symbol of perfect beauty, which he resents because he feels so fundamentally like he lacks it—a resentment that leads him to eventual destructiveness. Though over and over he states that he prefers to be apart from life, he longs for an end to his solitude and to have something in the world to be remembered by. Witnessing others live happy, regular lives nearly steers him off his destructive course multiple times, but he always convinces himself that their carefree lives would never be an option for him due to his otherness and therefore the only way to continue to live would be through destruction.

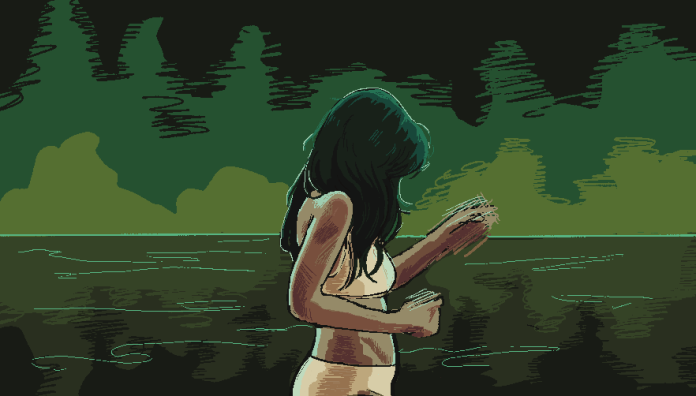

No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai

“No Longer Human” centers on Oba Yozo, who feels incurably alienated from others from early childhood and subsequently falls into increasingly heavy drug use and multiple suicide attempts before his dissappearance. In a story told through multiple journals Yozo kept throughout his life, he narrates his consistently paranoid and terrified view of the ways of human beings and all that keeps him from being one of them. Interestingly, this novel is semi-autobiographical for popular postwar author Osamu Dazai, and it’s easy to see the many points in which Dazai used this novel to communicate his own changing world perspective through his life. “No Longer Human” is the last book Dazai published before his death, which resulted from drowning in the river in a joint suicide, one of many attempts throughout his lifetime. Yozo, the protagonist of his novel, began “clowning” from early childhood to avoid angering others and distract attention from himself. Sexual abuse and parental neglect he suffered early on gave him a feeling of isolation and alienation throughout his life, which turned him to destructive path that often pulled others down with him. His outlook on the world briefly shifted to a view of society as inherently selfish, allowing him to focus on his base impulses for a while, but a shocking incident showed him the darkness of the world yet again. This final showing of evil in the world shoved him back into a terrified paranoia of the world and its inhabitants that he resided in until his disappearance later in life. Dazai’s depiction of the alienation of depression doesn’t exactly make for a beach read, but the book’s raw portrayal of mental illness makes the dark nature of the novel worth it.