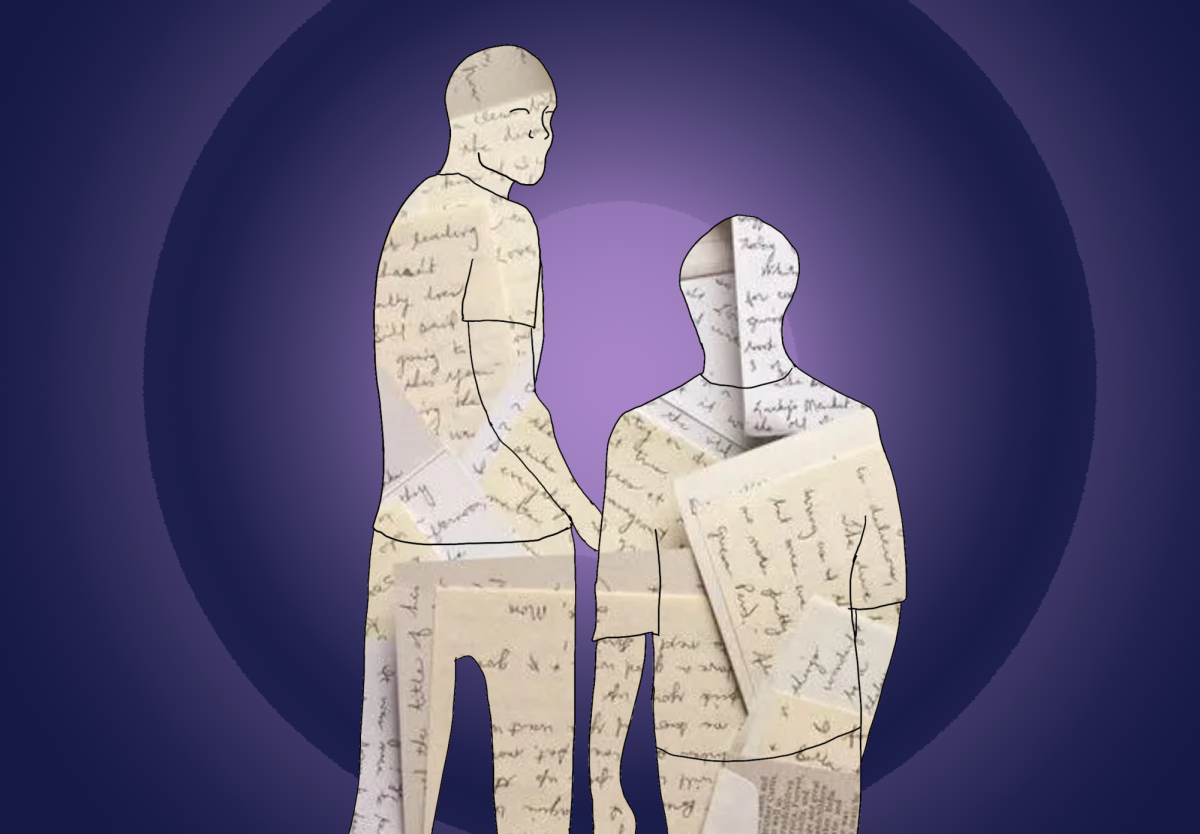

Eileen Dunlop is the all too self-identifiable wallflower, always watching and never seen. She is any plain-faced, girl-in-too-long-wool-skirt of 1964, repressed as equally in her sexuality as in her identity. Her life is bleak—as is she—until in an instant, her fate is changed.

Originally a novel by Ottessa Moshfegh, “Eileen” was notably penned as a joke in 2015 via a workbook claiming anyone can write a book in “just 90 days!” “Eileen” follows its titular character through the mundanities of a secretary job at a juvenile boys correctional facility in X-ville, Massachusetts. In the book, Eileen narrates as a woman late in her 60s, reflecting on the past—or, “the story of how I disappeared”—with an older, detached mind.

“Eileen,” the film, hit theaters December 1, but not to break any box office records. Starring Thomasin McKenzie as Eileen, and Anne Hathoway as enigmatic newcomer Rebecca, Moshfegh herself adapted the screenplay from her book alongside husband Luke Goebel.

Through film, Eileen’s internal fantasies have no choice but to manifest themselves onto the screen. She shoots her father. She shoots herself. It turns into a boy-who-cried-wolf sort of series of misgivings, coaxing the audience into a false sense of security everytime a gunshot wound cuts to what actually occurred. “Eileen,” the film, is a removed perspective of a story initially entirely driven by an inner voice. On the big screen—or little screen, as “Eileen” was only showing in Bend at the Tin Pan Theater downtown—that inner voice is gone. It is replaced instead with the metallic flicks of a cigarette lighter and the sputtering of Eileen’s fractured station wagon silently poisoning her with carbon monoxide.

The women of “Eileen” are all thudding against their glass cages, trapped in an idealized femininity that Eileen herself wants so desperately into. She’s exiled from the same uglies of womanhood that Rebecca and Lee Polk’s mother, Rita Polk, are trapped in. The same uglies that killed her own mother and sent her sister away.

The thing is, Eileen isn’t her dead mother in her expensive fur coats—driven to a suicide her husband is blamed for. She’s not her sister, Joanie, leaving home behind having faced her father’s drunken assaults. But nevertheless she aspires to be. In the book, Eileen salivates for violence. Violence sexually, violence mentally, violence physically; an overall masochist. It takes one final, real violent act to finally feel in control of herself. To feel the kind of control she thinks Rebecca, and all of these other women, have.

It’s a difficult thing when a story is considered first as a novel, and then adapted into a film, instead of conceived to exist solely for the screen. So much of “Eileen,” the film, is filled in by having read “Eileen,” the book. And sure, Thomasin McKenzie could have narrated the entire thing with her crispy Kiwi-laden Massachusetts accent. But that’s not the point of “Eileen.” It’s not a blockbuster film, nor a flashy thriller period piece. The film simply facilitates the narrative from the novel—an exclusive scarcity championed by only showing for a limited time at the one and only independent movie theater in town. It serves functionally as a companion piece, much like Eileen and her seemingly perpetual role of accomplice.