Every afternoon for the past few weeks, teachers sporting blue union t-shirts have been lining the sides of the Northwest Crossing/Mount Washington roundabout, picket signs in hand. Passerbys show support by waving or honking, thankful for the teachers of their community. Could these displays be considered the first warning signs of a strike?

The Oregonian reported in a recent article that as Portland entered the “west coast wave” of school district strikes, fellow school districts and teachers unions watched closely for the outcome. Now more than ever, the results of the Portland strike could have massive connotations in communities across Oregon as over 70 districts are negotiating contracts this winter.

As the Portland Teacher Strike comes to an end and nearly 45,000 students return to school, the movement for fair wages and a manageable workload has taken flight throughout teacher’s unions in Oregon. The strike lasted 26 days, 11 of which students spent outside of the classroom. With the announcement that Portland Public Schools were shortening winter break by a week, students have mixed emotions about the ethicality of the movement in the first place.

“[The strike] made me think about what teachers are going through because my mom is a teacher. I didn’t think it should have gone to a strike but the district wasn’t compromising,” said Emerson Tofel, a junior at Grant High School in Portland. “I don’t think it was a good thing for the kids because they came back disliking school more, knowing they’re taking away our winter break when we didn’t do anything. I think the district just f***** us and the teachers over.”

While tensions settle down in Portland, awareness around the similarities between Portland Public Schools and Bend-La Pine School District’s situations is rising. Teachers working for BLPS find themselves in a strange position: not wishing for a strike but only having a small window of opportunity to do so. A few Oregon House Republicans are beginning the push to make public school teacher strikes illegal, as highlighted in a Willamette Week article.

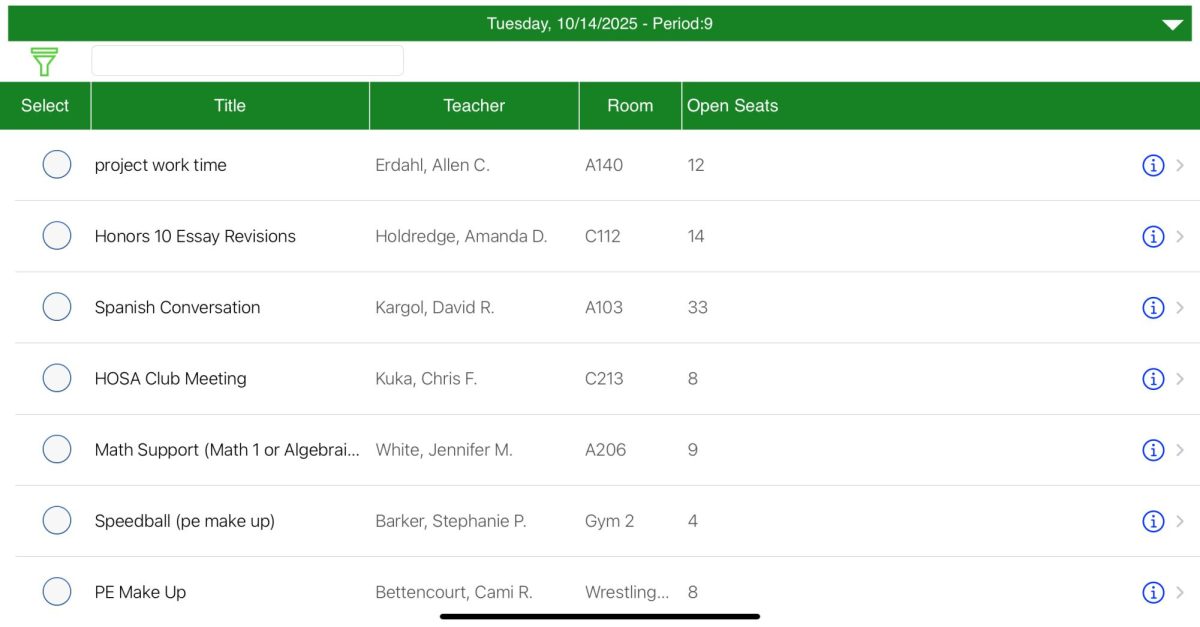

Bend teachers have been collaborating with district representatives in sessions called “bargaining,” which are hours-long meetings where teachers and the district work to find a contract compromise that is not only plausible for BLPS but also encompasses the teacher union’s requests.

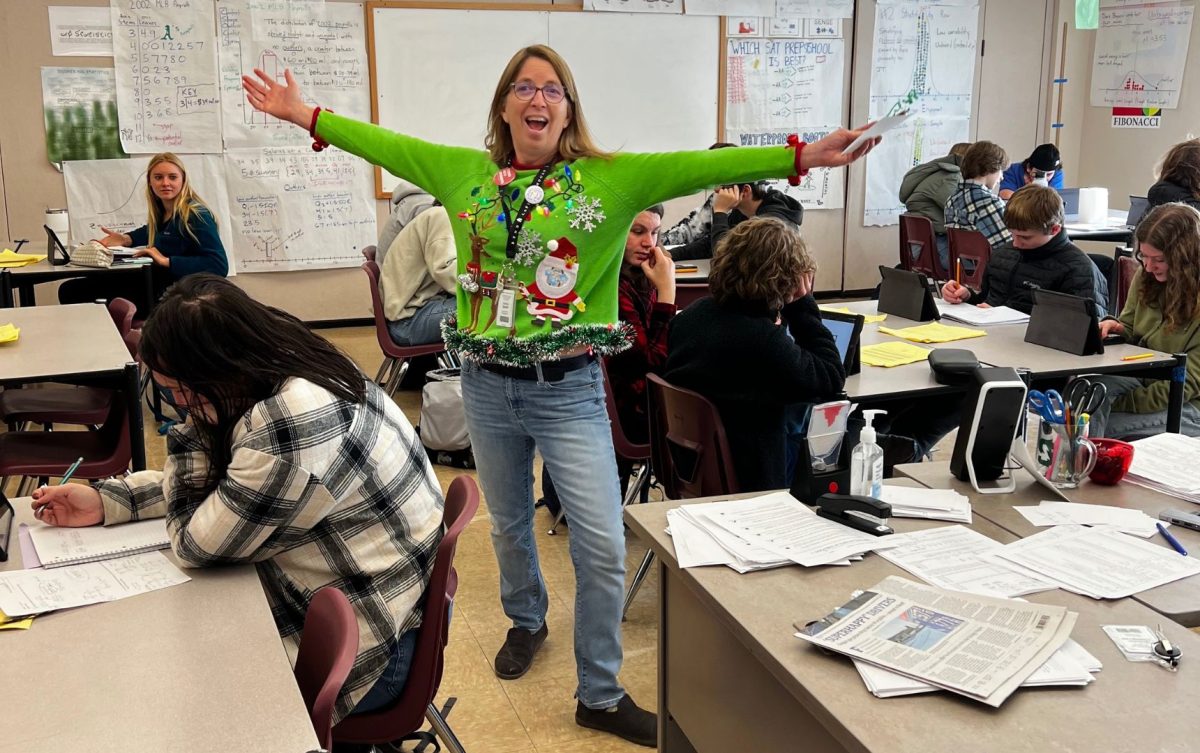

“We have been in [bargaining] for well over a year, and the bargaining process is like a never-ending process,” said Peter Borowski, math teacher at Summit. “So we’re gonna get to some resolution on this contract and then the bargaining groups, both the district and the union, are gonna resume the next contract.”

The fight for a fair contract is being tackled by representatives from two teacher’s unions: Bend Education Association and the Oregon School Employees Association. Educators working under the BLP district have requested adequate planning time, manageable class sizes and workloads, a fair cost of living adjustment, and safety and behavior protocols.

“[We are requesting clarity on] things like what would a typical work day look like, how much time would a teacher be devoting towards teaching in front of students versus how much time they may have to prepare,” Borowski elaborated.

Although the process began in May, the meetings are still in session this winter. District representatives seem confident that the union and themselves will come to an agreement by the end of the year, but OPB has highlighted just how far they really are from making a deal. Where Bend teachers have proposed a salary increase of 11 percent this year and 10 percent the following year, the district came back with an offer of less than half those rates.

This spring, BLPS will reach the two-year mark of the bargaining process for their new contract. The district is one of many stuck in this phase, some of which include Salem-Keizer district, Medford School District, Greater Albany Public Schools, Bend-La Pine School District and until recently, Portland Public Schools. The sheer amount of districts requesting a more equitable contract alone proves how important the issue is to teachers, and they aren’t the only ones who are passionate.

“I really saw the impact in pre-calc when we were talking about residuals and Mr. Thompson explained how much [teachers] get paid versus how much [housing in] Bend costs,” said sophomore Hazel Donnelly. “Talking about it and visualizing it really shows you how much we need change.”

As the bargaining process drags on, both students and teachers become increasingly concerned about the possibility of a strike and its consequences. Whether against or in support, nobody knows what a strike could look like for the district. Portland students missed 11 days of school and are making up for it during winter break, so it’s easy to assume Bend students would be forced to do the same by sacrificing spring break or even letting extra school days bleed into the summer. The fear of missing school and the risk of students falling behind is on everyone’s minds—parents, kids and faculty members alike.

Every day that passes without a strike announcement is both a blessing and a curse. At what point is bargaining just delaying the inevitable? The longer the district and teacher unions are unable to come to a compromise, the more likely it is that a strike will occur. Many students worry that the timeline of such a strike will directly interfere with their AP course, or even the exams themselves.

“I had friends who take AP Physics who had a test when they came back,” said Tofel, describing how for high-achieving students, having time off of school ended up being detrimental to their progress in advanced classes. On top of missing valuable days in the classroom, college-level courses move at a rapid pace, which a teacher strike would set back drastically.

“I’m worried about my grades in certain classes, mostly math and chemistry because I might forget important material [during time off],” explained Donnelly. “I can’t imagine how much the upperclassmen would be impacted because of the harder classes they’re taking.” All things considered, nobody wants a strike.

“I don’t think it’s good for any students, as first and foremost it’s incredibly disruptive,” explained Borowski. “All the teachers and all the district administrators have seen how difficult it has been on [Portland] and we’re all viscerally aware of its impacts, so we’re gonna do everything we can to avoid that.”