On the first day of the school year, students were introduced to strict phone policies in every class. The same slideshow (replayed five periods in a row) detailed the process of getting caught with your phone, starting with the first offense where your phone is taken to the attendance office for the rest of the day. The next offenses only got progressively harsher. Despite the dramatic start to the year, everyone rolled their eyes and shrugged the policies off, anticipating the day when teachers became lenient and restrictions inevitably ceased.

“I thought [the phone policy] was annoying, but I knew it would die in a month or two,” said Summit senior Tess Nelson. “That’s usually what happens.”

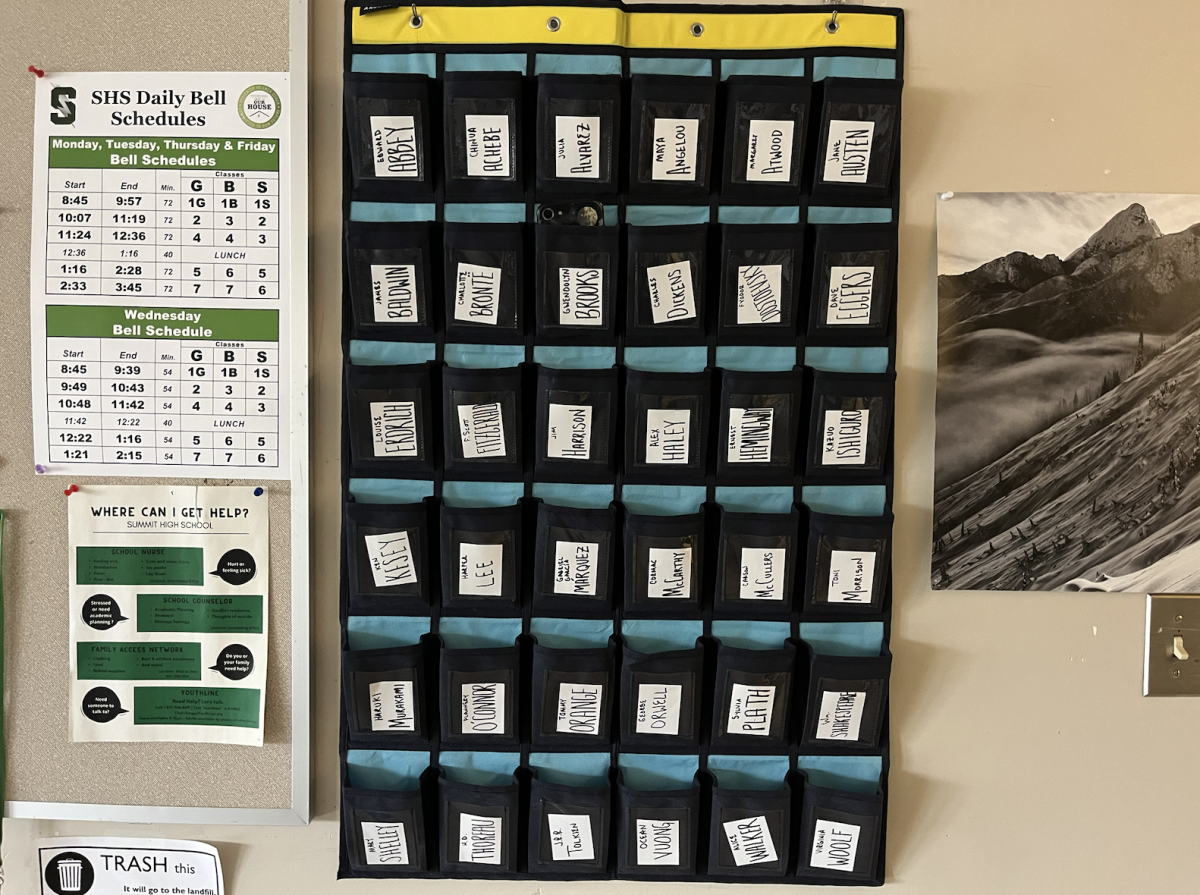

And a few months later, here it is—the fall of the phone pocket chart.

It’s commendable, really, that the policy lasted so long. The desire for focus and discipline in the classroom surges at the beginning of every school year, but the resolution always fizzles out.

“At first I was kinda just annoyed with it, but now that we’re so far into the year it doesn’t really matter,” said Summit sophomore Ethan Van Ess, having accepted the fact that he’s required to give up his phone in some classes, while in others the policy is barely enforced. The inconsistency between classes speaks to the larger idea that many teachers are unsure of where they should stand.

“We are all human and the path of least resistance is always easier than confrontation,” explained Travis Overly, one of Summit’s social studies teachers. It’s hard to maintain certain rules and restrictions because it requires many teachers to police their students, which is often a difficult position to be in. “Being on time, attending school and being distraction-free in the classroom for that matter, are habits that start at home and should be enforced by parents.”

“A lot of teachers have better things to do than manage an extra [phone] caddy. I think we’ve all decided it’s not worth it,” said Nelson. Despite this, Summit’s admin are hopeful that the school’s newfound cell phone restrictions can be reinforced via a reminder at the end of the semester.

“It’s all about constant revisitation,” explained Jamie Brock, Summit teacher and admin. “[Teachers] are busy, so it becomes easy to let go of some of what we feel isn’t that big of a deal.” Brock stressed that reviewing the phone policy at the end of the first semester was the key to keeping momentum going.

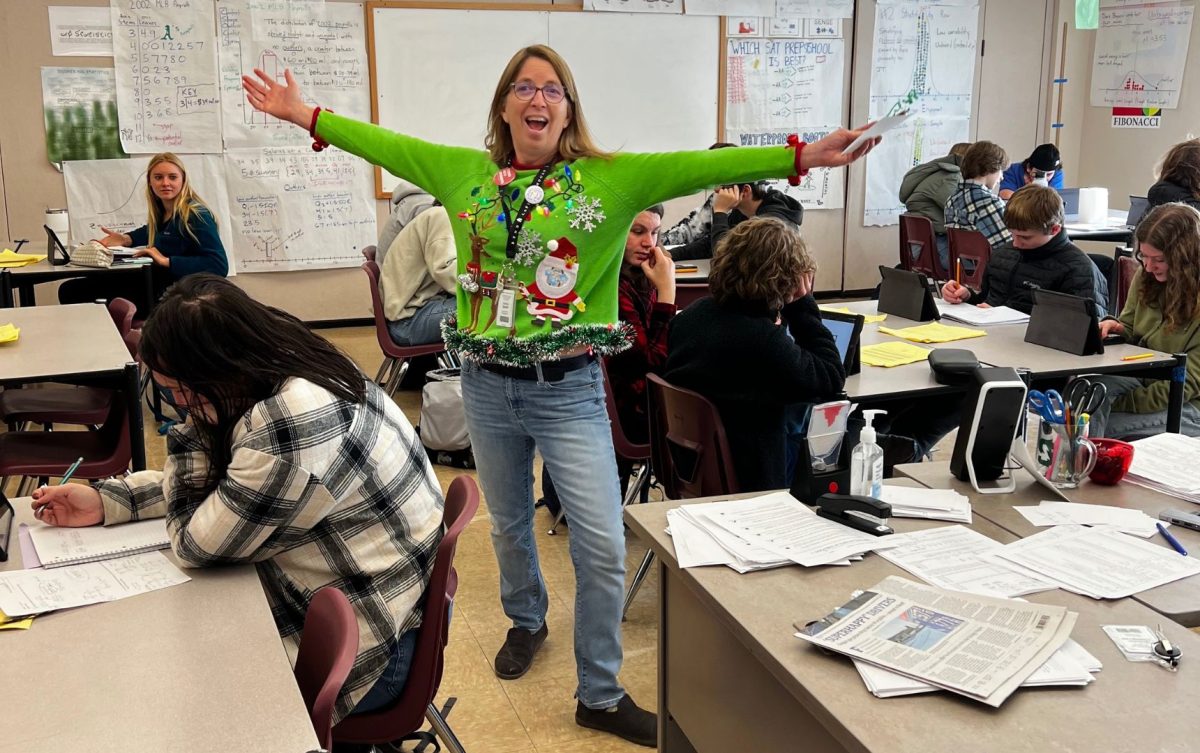

“I think the reason they may lose momentum is simply the energy and time it takes to maintain the expectation and continuously uphold the accountability,” said Thea Layton, Summit’s newest math teacher. “At the school that I used to work in, we have used cell phone caddies for several years. I think it’s a great way to separate ourselves from our phones and take away unnecessary distractions.”

Regardless of pushback, the cell phone policy (when enforced) keeps students from checking out. Although some teens don’t need distance from their devices to be engaged, those who do are able to be more present in class when their cell phones aren’t burning in their pockets. As restrictions die out, staff hope that engagement won’t go with it.

But will a reminder be enough? Just last year, the Bend-La Pine school district enacted a locked-door policy, in which all classroom doors were required to stay locked from the outside during school hours. The rule, meant to promote safety of students, ended up being largely disruptive, requiring teachers to stop lessons each time someone needed to be let back into the classroom.

Naturally, some classrooms adapted to the policy. A couple months after school started, magnetic lock blocks, wooden door stops or even just ‘forgetting’ to lock the door in the first place kept classroom entrances easily accessible. Once again, students were able to come and go as they pleased. But this is just one of several rules lost to negligence. The tardy policy was also recognized as a restriction that has fallen through.

“We just don’t have the capacity to put everyone who is tardy three times or more into lunch detention,” said Overly. On top of this, Nelson and Van Ess both described the lack of necessity for a bathroom pass when roaming the halls.

“If [the hall pass] is gone I’ll just go anyway, because I’ve never really gotten bothered,” said Van Ess. Even admin don’t seem to enforce the rule, as Nelson has noticed that they and many others have (without incident) walked past or had conversations with hall monitors without the pass in their hands. But what if this is exactly how it should be?

An article by Developmental Science emphasizes that the importance of autonomy protection and respect for teens only grows with age. Young adults cherish the freedom to act on their own volition, which gives them responsibility. Furthermore, this responsibility allows teenagers to understand that their actions are meaningful, and they need to be smart with how they decide to behave.

“Threats to teens’ autonomy may make them feel less able, less trustworthy and more childlike than adult-like. Autonomy threats also send negative messages about teens’ competence,” the article elaborated. When young adults are treated like kids that need strict rules, it enforces the idea that they can’t be trusted to make smart decisions and often shuts down teens’ willingness to collaborate or engage.

“I think with the new phone policy I want to be on my phone more than I did last year,” said Summit sophomore Joel Hoffman.

Open-door classes, being able to speak with faculty without the fear of reprimand, entering other rooms to pull people for interviews, discuss projects and ask questions… All of these things fuel participation and further student’s learning, and all of these things are impossible with the current policies in place.

Maybe it’s time to reconsider just how worth it some of Summit’s policies really are.