The War On Traditional Grading

Summit teachers express concerns over possible grading change.

Students file out of a classroom. It’s a Tuesday, and their teacher is left with 30 more tests, in total reaching to more than 150. Instead of being a multiple choice test—which is quick to grade—the test is short answer based, with students writing down what they know for each question. Marking down what’s true and what’s false and equating it to point value is nonexistent: instead, teachers grade based on a rubric, scanning through paragraphs of work to find an answer. This is the reality for many teachers at Cascade Middle School, which uses standards-based grading for their students.

The idea of “modern” grading is becoming more popular with districts around the country. Proponents are arguing against the standard letter grade in favor of a more personalized system: one that would completely overhaul traditional grading.

Bend La-Pine is no exception.

“The shift from traditional grading to standards-based grading is that instead of a point-based system, students are scored in relation to where they stand on state standards,” said Cascade Middle School’s principal Stephan DuVal. Instead of being graded on the amount of questions answered right, students would be assessed based on their ability to demonstrate the skills necessary for that course.

Grading systems such as standards-based and proficiency-based learning—which follow similar rules—are rapidly becoming popular concepts. These standards are already being used in elementary schools and some middle schools throughout the district, using a 1-4 grading scale to assess students on individual proficiency level to state standards. The main difference with these grading systems is that they allow test retakes; proficiency allows as many retakes as possible, and standards allows a few with strict guidelines.

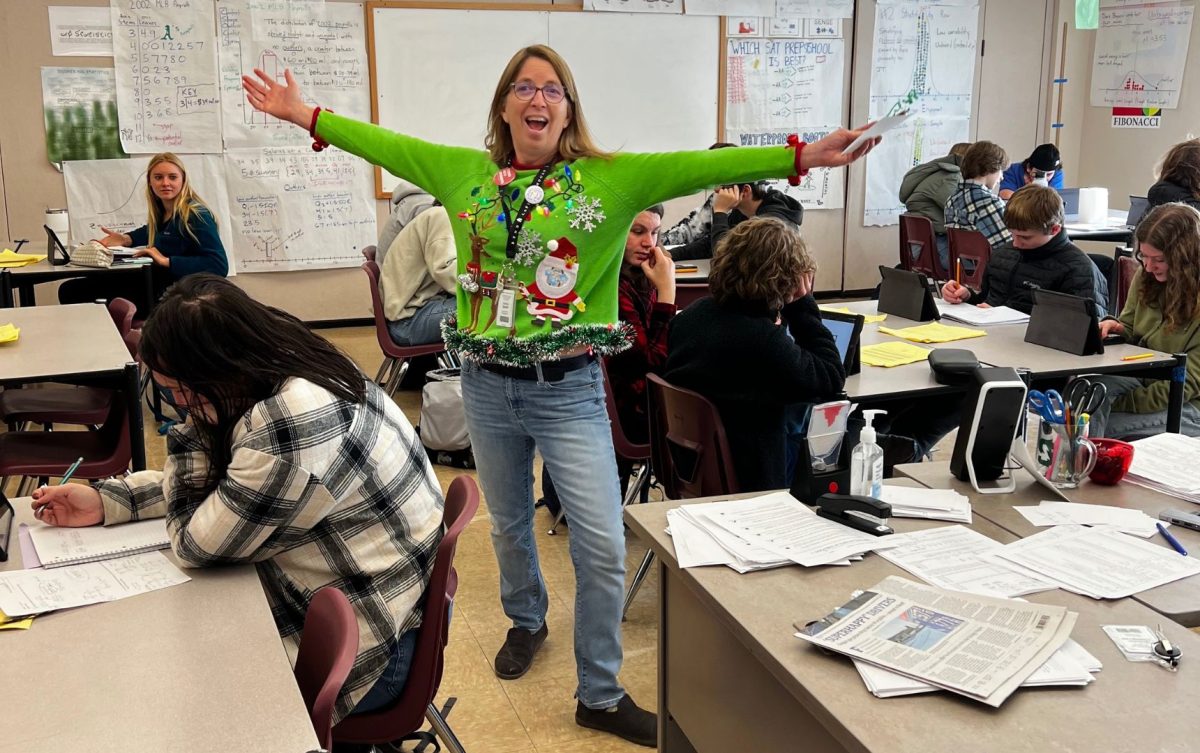

The main concern with standards-based grading? Teacher workload. “I think that a lot of things that are done in a middle school don’t translate well to a high school,” said Erin Carroll, a teacher at Summit High. “And when we talk standards-based grading, I know that it’s possible to do in a high school. But I think asking teachers to totally rework their grading scale, with minimal time to do it is not going to be ideal.”

Teachers shared a common sentiment: in an ideal world, standards-based grading would be better for their students as individuals.

“I have—like a lot of teachers—I think, some pretty big reservations,” Carroll said. Despite good intentions, standards based grading, or proficiency based grading, just sounds like a mountain of more work to grade.

“I think that, given the teachers-student ratios at the schools in this county, I have a hard time seeing it be an effective method,” said Frank Brown, an English teacher at Summit. For teachers with 200-plus students, the idea of having to regrade hundreds of tests or assignments after they’re due is daunting. For teachers with 30 or less students, they can easily manage personalized grading.

Concerns from teachers haven’t deterred the conversation.

“I think it’s already happening,” said DuVal. “You know, there are some things with GPA rank and things like that that need to be considered when you do the work, but those aren’t obstacles that can’t be overcome to shift this direction.”

For teachers, ‘obstacles’ like these are more daunting.

“I think I could implement standard based grading in my class. And ideally, it wouldn’t be much more work after I got it going. But when it then comes time that I have to give them an actual grade, that’s when there would be a lot of work put on teachers to translate that,” said Carroll. For many teachers, they’re in a difficult spot: trying to make grading more equitable, while also being aware of their own workload and the consequences that come with it.

“I think for the teachers that I’ve talked to in this building, that switch, I’m all for making my classroom and grading the most equitable that it can be. But at the end of the day, when I have to give a letter grade, is this really saving time? Or is it just causing more confusion?” Carroll said.

“A team of teachers, Summit High school teachers included, are having conversations around best grading practices and what the research shows in an effort to improve our systems. So that’s happening right now.” DuVal said.

Despite good intentions, personalized grading systems are inherently flawed, and only time will tell how it pans out.

“Mom, I finally made it in the newspaper! Are you proud?”

A brilliant mind and philanthropist, Adri enjoys classical music, regular music, rock music and all other types of music, as well as various...