The Invisible Wall Between the Students and the Counselors

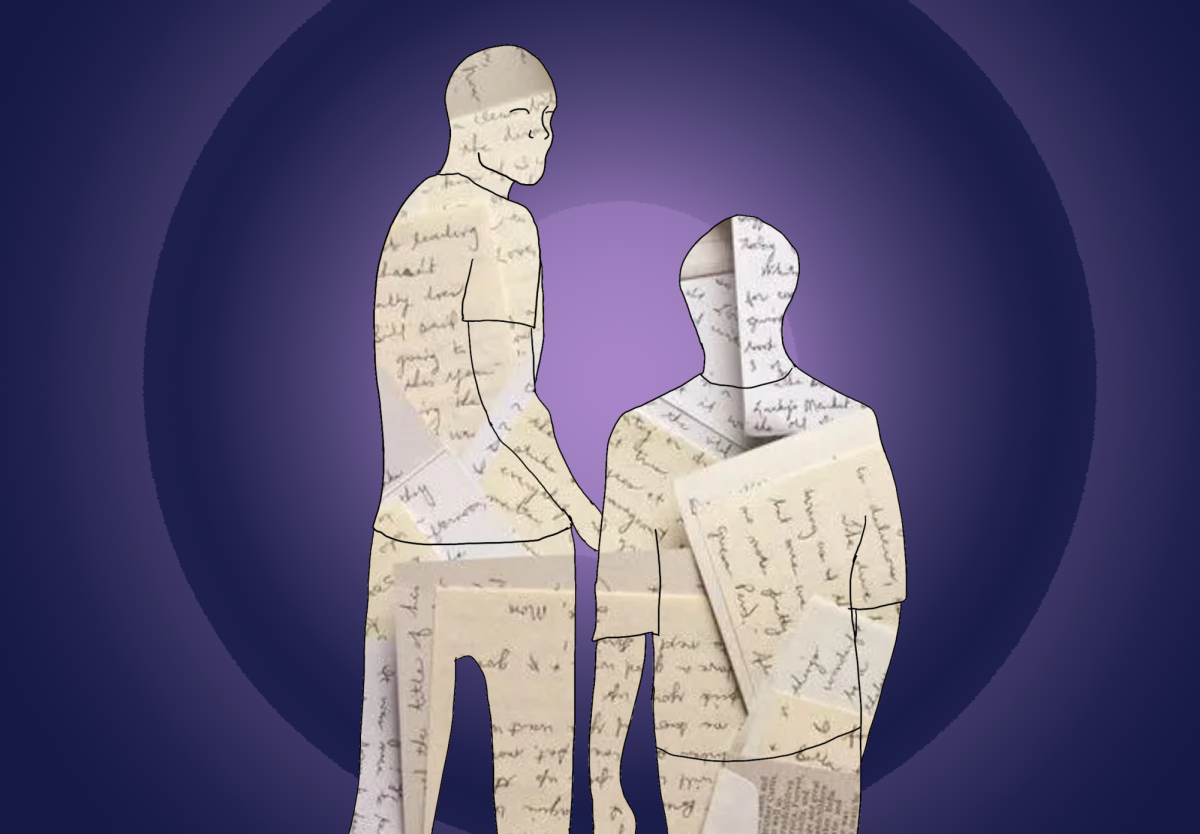

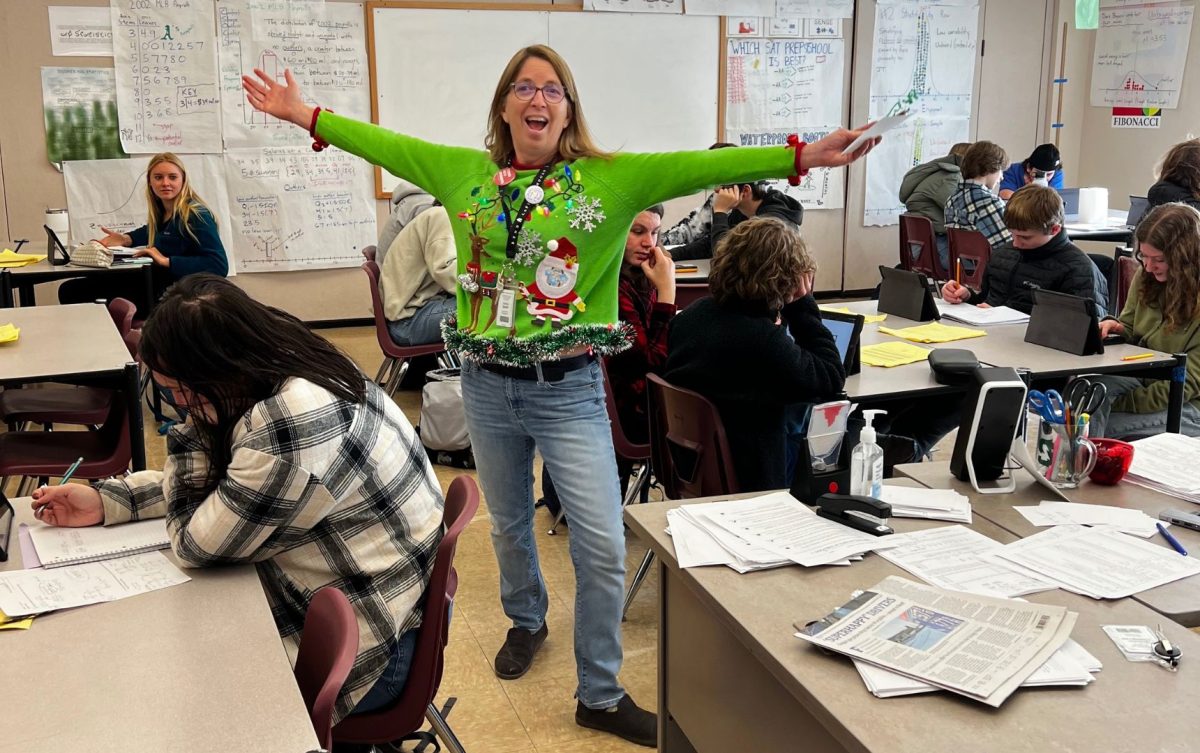

Summit’s counselors are as integral to the Summit experience as the phrase “Sko Storm!” and the lack of functional locks on the bathroom stalls. That is, Summit wouldn’t be Summit without them. Wearing more hats than the entire Kentucky Derby, the counselors oversee the social, emotional, and academic wellness of the entire student body. However, with approximately 400 students each and the Bermuda Triangle of responsibility on their plates, it isn’t surprising when students don’t get the personalized attention that they often need.

“We help support students in the social emotional wellness piece, and that is… what a large part of our jobs are,” said Carla Gomez, one of Summit’s five counselors. “But what happens in the real world of school counseling, at a high school in particular, is that the academic health piece sometimes tends to take over a lot more of our time.”

This shortage of counselors has far-reaching consequences, and has left many students feeling disconnected and thus less likely to reach out when struggling.

“They [counselors] don’t feel connected to the student body at all, they just seem to kind of be there. They go in their offices and they don’t talk to us,” said junior McKenzie Sentena.

But the overwhelmed counselors, who are often just keeping their heads above water, see it differently.

“Nothing’s perfect. We try, but people are gonna perceive things how they do even though we try, they might not ever feel like we’ll be a viable resource. It can always get better,” said counselor Karen Luke.

There is no doubt that the counselors are both good at their job and eager to help: “I was very surprised at how welcoming the counselors are, because I think the whole discrepancy is just getting through the wall,” said senior Shayna Kohl, who was urged by family and friends to make contact during her freshman year. “Once you’re through, my counselor helped me through so much. I could sit in her office for as long as I needed, and she never kicked me out.” Kohl encourages her fellow students to pay a visit to their counselor in the hopes that more students can have the experience that she did.

However, the counselors themselves have never been the defective variable in the broken equation of counseling at Summit. Instead, it is a systemic issue, plagued with understaffing and disjointed communication.

The counselors’ method of identifying struggling students—namely, relying on teachers or parents to recommend cases while also leaning on a few measly barometers of mental health—is the first brick in the invisible wall between students and counselors. This method leaves many students out in the cold, allowing them to slip through the cracks and silently suffer.

“We would have no way of knowing unless we were just meeting with a student, or noticed that their grades were dropping, or they weren’t attending,” said counselor Karen Luke. “They do some things in Wellness where they take surveys, so that’s how we call some kids in.”

My personal experience proves just how easy it is to go unnoticed by the counselors. I was severely depressed for most of my sophomore and junior year, and panic attacks in the bathroom were part of my daily schedule. Despite my mental health being anything but healthy, I presented as an active, engaged student during class, with a 4.0 GPA and perfect attendance. I hadn’t taken Wellness since my freshman year, so I definitely wasn’t responding to any surveys. Even if I did, I likely wouldn’t have been candid about how I was feeling.

As an upperclassmen with good grades, I completely circumvented the counselor’s radar and my mental health paid the price.

Logically, the next step is for me to reach out to them. However, the idea of signing up for a meeting never even entered my mind as an option, leaving me invisible to the counselors and them invisible to me as a consequence. As one of the rare students who religiously checks my school email and actually pays attention during Forecasting and assemblies, I have difficulty accepting that I am solely responsible for going unnoticed. I, like many students, fell prey to the counselors’ failure to present themselves as a resource for non-academic issues. However, even students who are aware of the counseling office are reluctant to reach out, yet another testament to the student/counselor disjointment.

“I guess I just kind of see counselors as a thing for classes strictly,” said senior Jacob Zhao. “Part of it is that I feel kind of bad for them that they have so many students to manage, so if I have a mental health crisis I know that I won’t get the most personalized responses or treatment.” Though a kind sentiment, sympathy for the counselors’ workload shouldn’t prevent students from reaching out for help. It’s their job, and therefore it’s also their job to deal with the issue of understaffing. Students shouldn’t have to pay for administrative issues that aren’t our fault. Even Kohl, who had a positive experience after reaching out, has picked up on the disconnect.

“Unfortunately, and I wish it could change, there’s this idea around school counselors that because they have so many students to deal with, they don’t really give you the benefits and attention you might need,” Kohl said. “I feel like they [the student body] don’t take it seriously, and I don’t blame them considering that each counselor has 400 students to deal with.”

Timeliness is another factor that is influenced by the untenable student-to-counselor ratio, and one that plays an integral role in a student’s decision to utilize the counselors. The counseling department’s leisurely responses are infamous among students, and a substantial bulwark for those who need immediate help.

“I think there’s a general atmosphere that the counselors are competent, but they are slow,” Zhao said. “There’s an understanding that the reason the counselors are slow is because they have so many classes to keep track of and are always having to juggle a million tasks, but it is really frustrating.”

Punctuality can have serious repercussions for students who are having an immediate mental health crisis, and need swifter help than an appointment in the distant future can offer.

“If it’s an emergency then we try to tell the students they just need to tell the counseling secretary and she’ll get you right in,” Luke said. “Usually she can tell when they walk through the door… she’s good at reading that. Usually they’re close to tears, or they’re breathing heavy, or whatever is going on and she comes back and immediately gets us and goes ‘we have a student out here who’s really upset.’”

Though effective in theory, the system is nowhere near foolproof. Last year, Sentena was urged by her teacher to go to the counseling office after having a panic attack in class, but wasn’t able to get in contact with her counselor.

“I told her ‘hey, I’m having a panic attack and I need to talk to my counselor right now’ and she’s like ‘just put your name on the list!’” Sentena said. “I was crying and hyperventilating, because that’s what happens to me when I have panic attacks.” Sentena never got called back to the counseling office, and says that she probably wouldn’t turn to the counselors again for help. Instead, she would pay a visit to Mr. Nyman, Summit’s Skills Support Specialist.

“If you’re struggling, you can just go to his door and knock and he’ll be like ‘oh yeah, come in!” Sentena said.

Nyman, who has a Masters in Social Work, was hired in 2017 to help the counselors handle student’s mental health.

“The school counselors are trained in mental health, but they have very large caseloads and their work in helping students with their schedules and college readiness keeps them extremely busy,” Nyman said.

There is no other position like Nyman’s in the Bend La-Pine School District, making him an invaluable resource at Summit. Despite his expertise, and demand for his services, Nyman is still shrouded in anonymity at Summit. Any record of him is noticeably absent from the counseling department’s page on Summit’s website. I wasn’t able to find his email, phone number, or mention of his position anywhere. His name is mentioned once on the entire website, and it’s in reference to a group photo of the counseling department.

Nyman’s invisibility translates to the student body, where neither “Mr. Nyman” nor “Skills Support Specialist” rings any bells. “Smiley guy with the birkenstocks” warrants a bit more recognition among students, but Nyman’s hallway friendliness is where knowledge of him begins and promptly ends.

“They need to tell more people about the counselor who’s actually there for mental health, because I didn’t know about it at all until he requested to see me,” Sentena said. “More people need to know that he exists, because he’s really good for mental health.” Nyman’s existence at Summit implies that the school is quasi-aware of the counselors’ shortcomings, yet they still aren’t broadcasting the rare, desperately-needed resource they have deigned to splurge on.

The expectation that Summit would provide adequate counseling to students in times of struggle is not unreasonable. While I realize that budgeting is an omnipresent issue (this is public school, after all), so is a student’s mental health. Student crises won’t wait until the new high school is built, until an overeager booster makes a donation, until Gov. Kate Brown gives us a Hunger Games-esque grant for counselors galore. The Summit student body is—and has been—struggling, yet it is easier to ignore the deep-rooted systemic issues in favor of a scheduling clipboard and colorful PowerPoints during Forecasting.

The road to hell is paved with good intentions, and Summit’s counseling system is dropping those pavers in place one at a time.

When Barbara Norton isn’t editing articles for The Pinnacle—alongside her marvelous, incredible, breathtakingly savvy editors-in-chiefs Julia Burdsall and Viansa Reid— she most likely has her head...