Everyone is obsessed with the past, including me. I thought I understood why, but now, I’m not sure that I do.

It has become a common practice to listen to music, watch films, take photos, and even make phone calls in the… least technologically advanced manner possible. We collect records, CDs, cassette tapes, VHS tapes, film cameras and flip-phones as if they’re the new hot product on the marketplace.

Something-teen-year-olds who adorn the baggiest jeans they can get their hands on, ravage over original pressings of 2008’s “808s and Heartbreaks,” despite having access to every bonus, deluxe, redux and re-release from the past 200 years. In fact, between Spotify and Apple Music, we have access to more than 200 million songs. It’s pretty expansive if you know what to look for, but the genuity so many find in a roll of film or a vinyl record is lacking. It could be decision fatigue, but this regressing timeline is likely a part of something much bigger.

Distributed by Columbia records, the RPM LP vinyl record (essentially the records we know today) came about in 1948, offering a commercially viable alternative to the prior—extremely fragile and unreliable—shellac records. Similarly, In 1975, Kodak introduced the first digital camera, with sharp images and technical freedom. Most of the physical capture and display methods for both music and film were deemed unviable by the mid 2000’s, with just under one million units of vinyl records being sold in the USA in 2006. Now, as of 2023, over 49 million units sold, a massive increase in just 17 years.

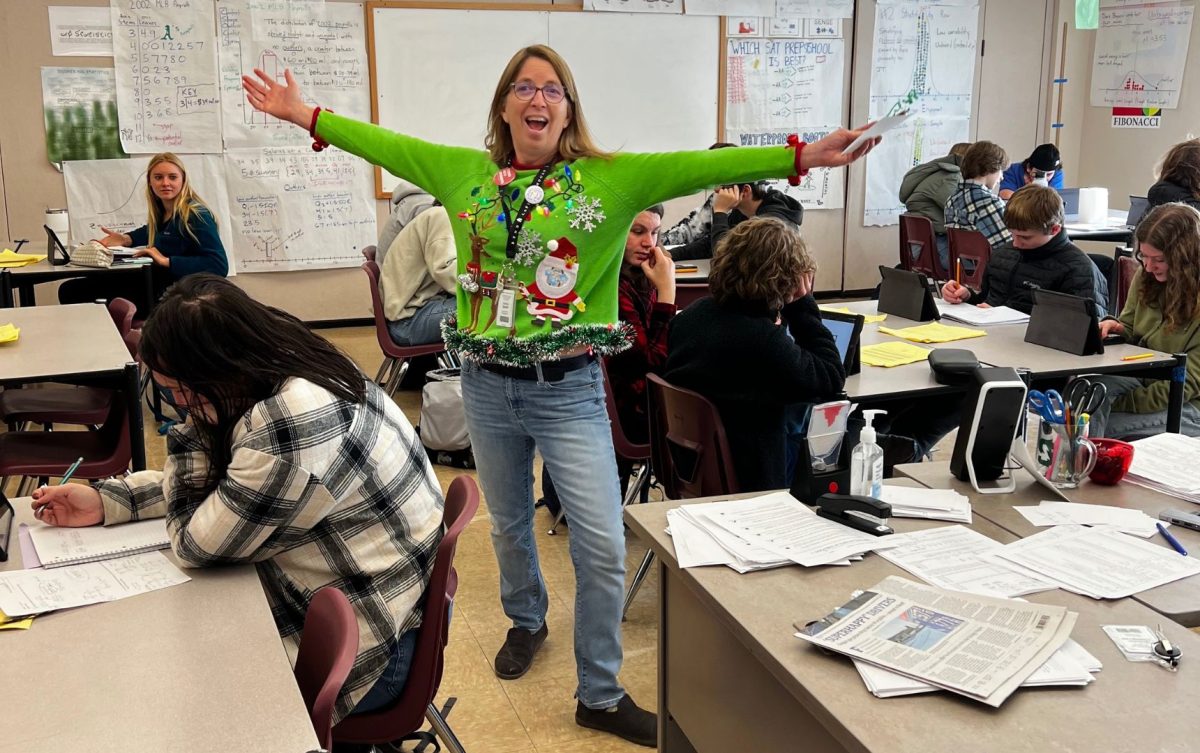

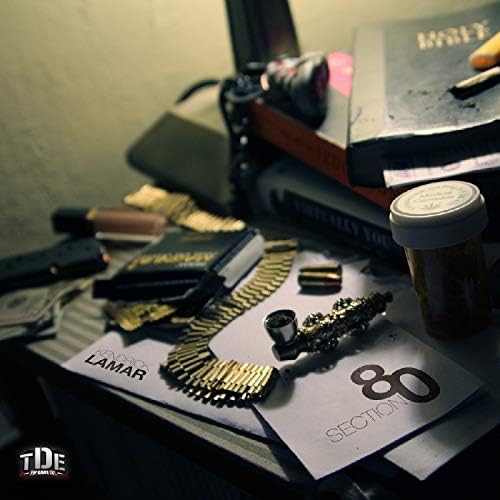

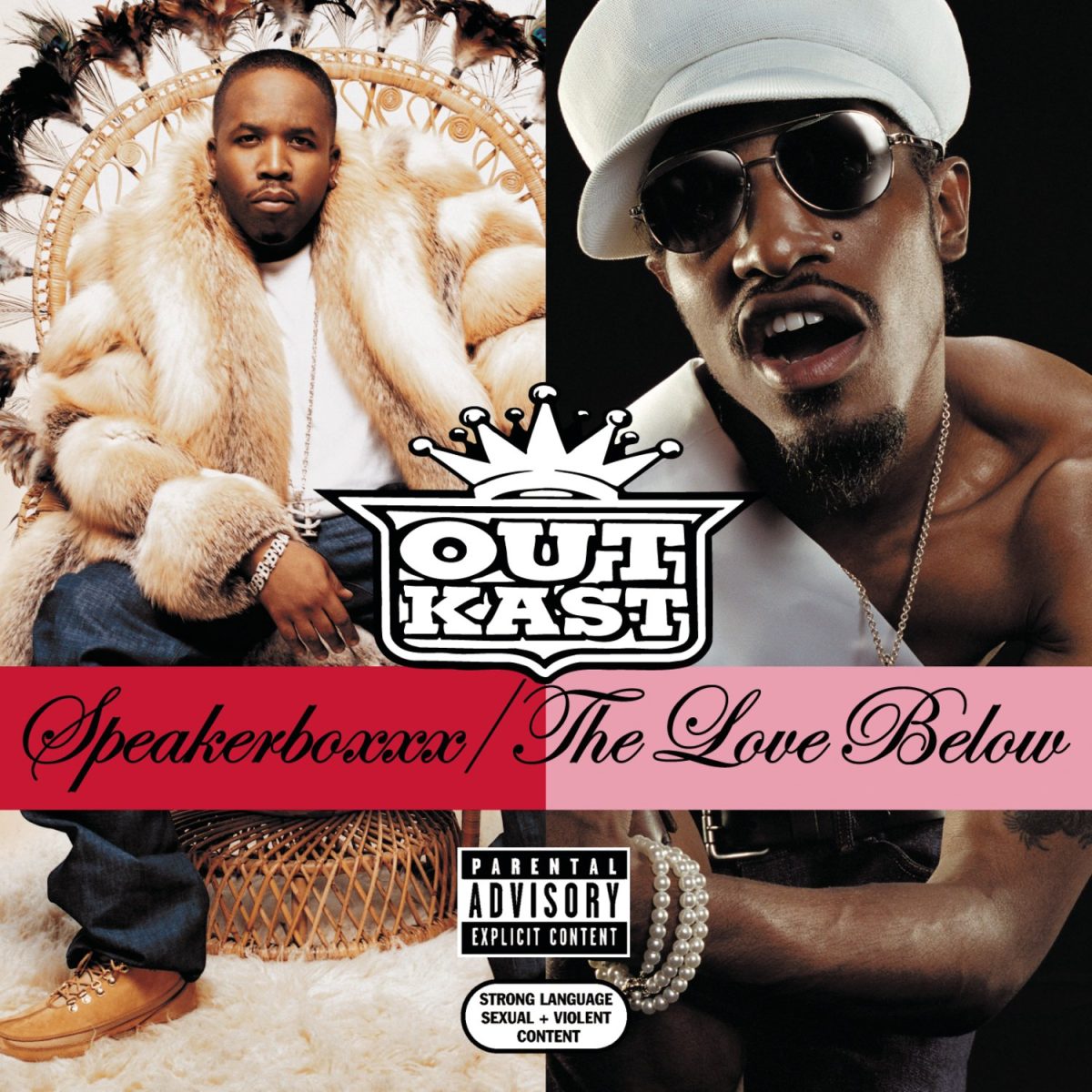

This revert is happening everywhere I look. It’s happening to me. A pile of books at the foot of my bed has replaced my monthly Audible subscription. An entire section of my 4×8 IKEA bookshelf has been invaded by an alphabetized and dated spread of 72 vinyl records, ranging from Kendrick Lamar to The Crykle.

It’s seemed for the past four-ish years of my teenage life, with my scattered range of interests, that this revert was a given. The records are plenty stylish on my shelf and the books make my room feel like a scene from “Good Will Hunting.” It just makes sense. But when I was recently asked why I spend time, money and space on products I have full digital-access to, I admitted— I don’t know.

Why would we want to go back in time? We live in the most technologically advanced Tesla, iPhone, Chat GPT, YouTube TV, smart fridge era the world has ever seen. We have complete access to everything– yet it kind of sucks.

It’s incredibly overwhelming that I can figure out how many songs are on Spotify and Apple Music with a 15 second Google search. It’s also incredibly overwhelming how many songs are even on Apple Music and Spotify. You can create a museum-ready painting in two minutes using AI. It’s exhausting how extensive our tools and capabilities are. I don’t want everything all at once anymore.

True connection becomes impossible when you’re consuming everything at once. When everything looks and sounds like its contemporaries, art blends into a grayish camo of ultra-clean pop radio background noise, explaining the appetite for the texture of all this old stuff.

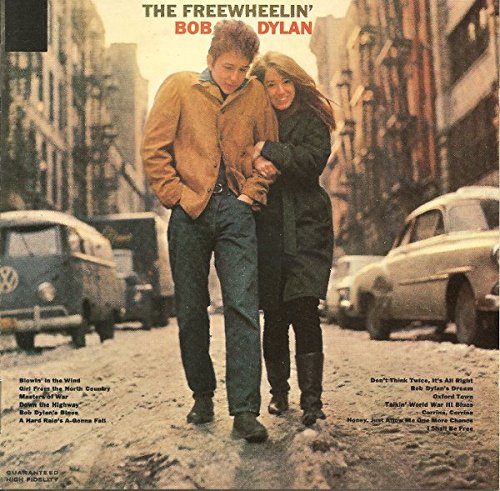

The tangible actions involved in physical media alone counteract the harsh saturation of digital consumption. The trip to the crates to dig for your favorite record, whether it be Bob Dylan or Freddie Gibbs, unearthing the record itself, dropping the needle, flipping the shiny plastic plate every twenty minutes or so; It all works to include the audience, grounding listeners for the ride of the chosen album. There’s no skipping songs, no fast-forwarding to the hook—just you and the music as intended.

Even my own best friend, who is far removed from the indie-art culture that stemmed the record-revival, has begun collecting his favorite albums and employing them as modest wall art, a personal trophy collection of music.

I recently rewatched “Call Me by Your Name,” a charming ballad of a love-struck teenager in mid 1980’s Northern Italy. The film is visually and aesthetically stunning, offering staggering illustrations of a simple life of reading, swimming and playing the piano, all documented on 35mm single lens film. This movie, taking place in the mid 80’s, feels eons more refreshing than the latest MCU hyper-synthetic superhero jargon taking place in 2099, and it’s not solely because of the plot or the aesthetics.

Films like “Call Me by Your Name” are emotionally captivating because of this revert to analog capture. The camera feels invisible, offering an entirely personal experience of the narrative. You are in a small Italian town, smelling the smells and seeing the sights. It feels achievable; it feels real. It’s largely this warm sense of authenticity and intimacy that draws audiences in a cold world of $150,000 Arrieta Alexa 65 IMAX cameras.

The same goes for music. The scratch of a cassette’s magnetic tape, worn over the years, tells vivid tales of the times it’s been played before. The crackle of a well-loved vinyl record explains the music beyond its surface level sonics. It’s all become tangible. Something you can feel, hold and experience beyond its original meaning. Physical versions of what are now considered digital products wrap viewers and listeners in a warm embrace of personal connection.

So, until this too grows tired, I and many others will continue to embark upon the art that captivates us to a greater depth than which is offered in today’s age. In a world of everything, I’ll always choose something. And I think you should as well.

Jud Blakely • Apr 16, 2025 at 4:52 pm

Finn,

Your granddad Dick has told me about you and sent this to me. Dick and I were Class of 1957 at Duniway. I’ve been writing on American culture and politics for 50-some years. Your insights and gifts of expression are stunning.

I was Class of ’65 at Oregon State, then served 5 years as a Marine infantry officer with a 13-month tour in Vietnam.

You can’t write either well or with integrity if you don’t know how to think. In that regard, I believe you have a great start. I’ll be glad to communicate with you once you check with Dick. Note: I’m a “take no prisoners” guy.

Semper Fi,

Jud Blakely

Daphne, AL

Judy Mimnaugh • Apr 16, 2025 at 2:00 pm

I think this is your best piece, Finn Gober!