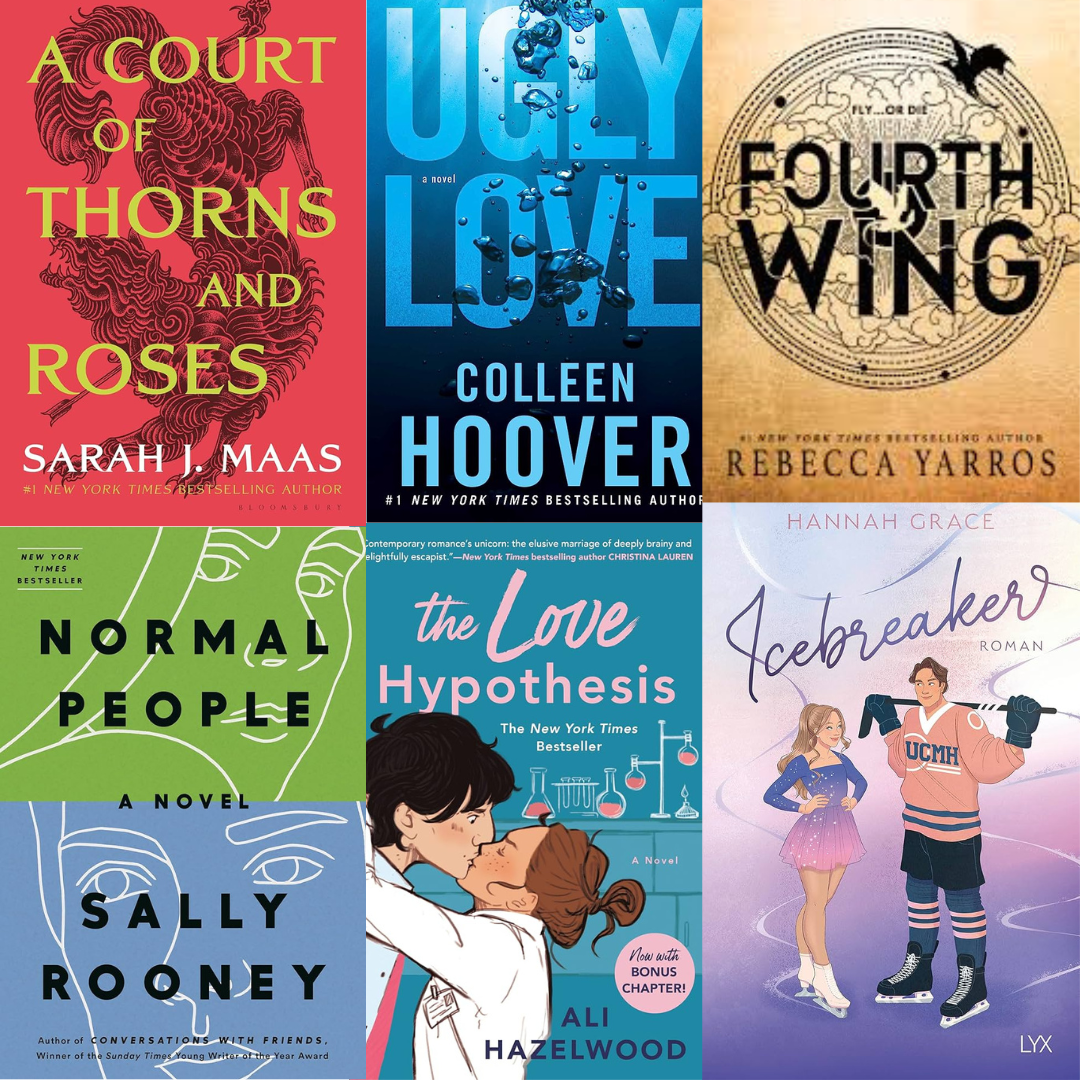

I first picked up “Normal People” in an AirBnB over the summer. A navy clothbound hardback, stripped of its dust jacket with silver letters down the spine. I was in New Zealand, of all places, and had already finished all of the books I brought with me on the flight over. What is arguably Sally Rooney’s most notable novel stood out on a shelf boasting Colleen Hoover’s “Verity,” various outdated Waiheke Island travel guides and a handful of more porny paperbacks.

I was warned to prepare myself heading in and I was ready for complete and utter devastation. What I found was a mirror.

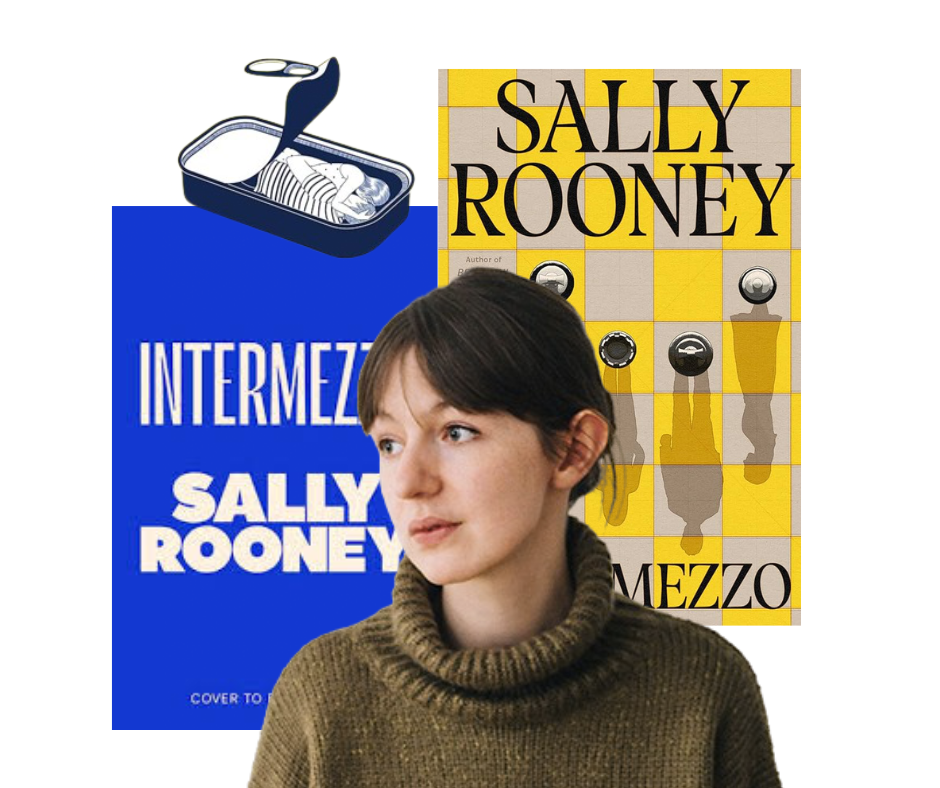

In the book world, Sally Rooney has been built up as a kind of 21st century literary deity. Considered a foremost millennial author, transcribing two of her three novels to screen, Rooney has achieved levels of success every young writer hopes and dreams for. The woman responsible for “Normal People,” “Conversations With Friends” and “Beautiful World, Where Are You,” is defining the literary scene for a new generation.

Before picking up “Normal People,” Sally Rooney was already familiar to me. I knew I was the exact kind of person that would read her work: an angst-ridden teenager with too many books on my bedside table, big fan of self-cut bangs and iced coffee. And yet, I had never picked up anything of hers.

“If you read Sally Rooney, the thinking seems to go, you’re smart, but you’re also fun,” according to Vox. “And you’re also cool enough to be suspicious of both ‘smart’ and ‘fun’ as general concepts.”

Critics attribute reading Rooney as a symbol of status, as a “cultural signifier” if nothing else. But there’s matching validity in that argument pertaining to Proust, or concerning the Dostoyevsky paperbacks peeking out of fresh-pressed New Yorker tote bags — never to be opened, rarely to be touched.

I was the Rooney Reader™ prototype, but I turned it almost into a quiet defiance of popular media, refusing to read her work just because everyone else was and because I didn’t think I’d understand her lack of quotation marks.

Nevertheless, I had some idea of what I was getting into. Sally Rooney’s second novel, longlisted for the 2018 Man Booker prize, I knew “Normal People” was sad before I read it. It was already familiar to me. Multiple friend’s favorites, I’d been sent a passage of main-character Marianne’s monologue reminding them of me. I’d seen clips of the Hulu adapted mini-series pop up on my feed intermittently and I knew that Daisy Edgar Jones was Marianne and Paul Mescal was Connell — I’d seen the Met Gala picture. What I knew was that the story was human and real, and frustrating, if nothing else.

Of course, I read “Normal People” and decided instantly that I was Marianne. I assigned an ex-boyfriend to Connell’s character, and took a personal affront to every step of their relationship.

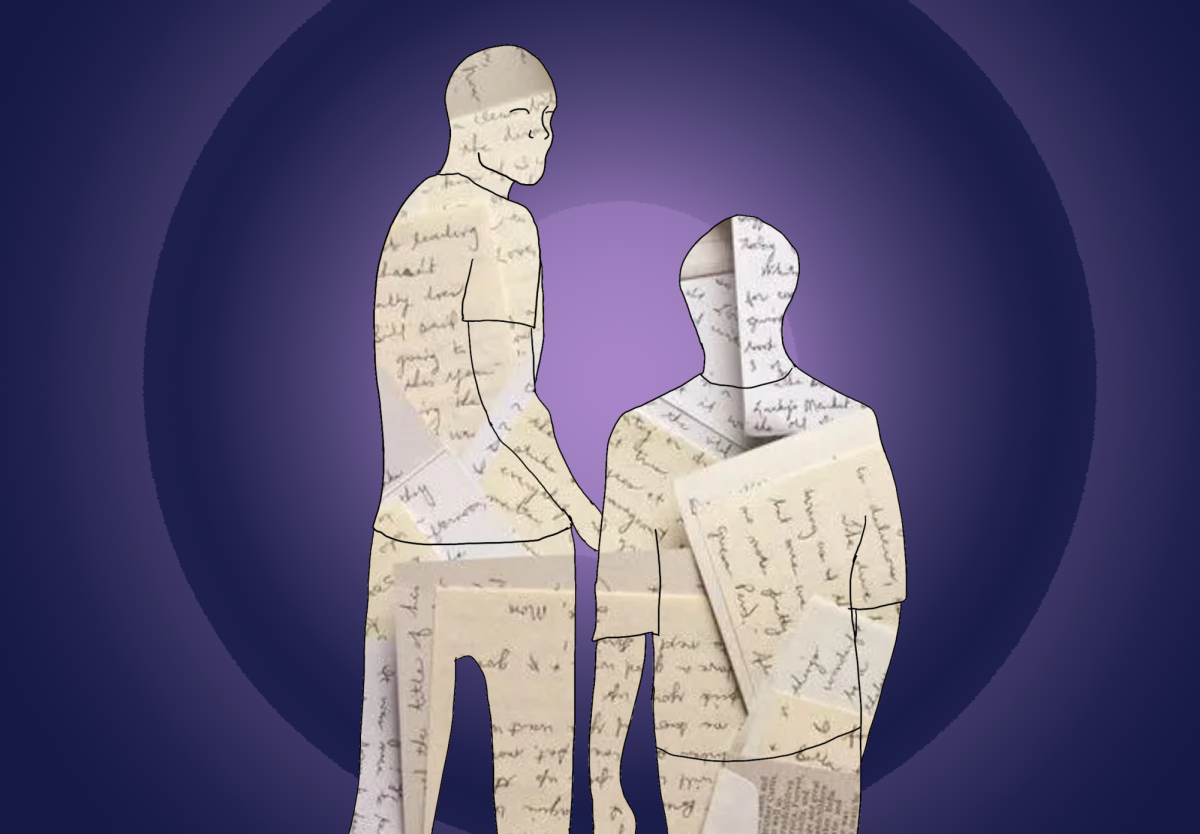

Throughout the book, Marianne and Connell’s connection is assailed by personal struggles and a general inability to communicate with one another. They push and pull at school — Marianne small and quiet, Connell cushioned by his incestuous group of friends — and in college their roles switch. Marianne finds herself while Connell crumbles. But the book’s shining, luring rarity is an ever-elusive two-sided perspective at a relationship.

Rooney’s new novel, slated for September release, shifts away from her doppelganger girls — all mousy brunettes, all fiercely political, all reflections of their author — and focuses instead on two brothers. “Intermezzo” is described as “an exquisitely moving story about grief, love and family — but especially love — from the global phenomenon Sally Rooney.”

What is automatically expected from the forthcoming “Intermezzo” intensely aligns with Rooney’s previous works. The idea of an intermezzo, that connecting instrumental in an opera, conceptually speaks to so much of what her writing is all about. Exploring the sinewy tissue that connects lovers, friends and now, in her new book, brothers.

“I don’t really believe in the idea of the individual,” Rooney said in a New York Times interview. “I find myself consistently drawn to writing about intimacy, and the way we construct one another.”

Rooney uses sex as a literary device — likening writing sex scenes to writing dialogue — and these books revolve around relationships. Any pain is written in tug of war with the love, with the sex. Her characters rarely do the right thing, navigating life as messily as seems capable. They can’t help that they’re in love. That’s where the charm is: in the flaw, and subsequent lack of consequence.

At the end of my trip that summer I found Rooney’s first novel, “Conversations With Friends,” at a bookstore in Sydney. I spent my flight home with it, and finished in the Sea-Tac airport sitting on the floor. Our flight was delayed from too much fuel in the aircraft — something that I didn’t know was a thing that happened — and I wrote down fleetingly in my phone that often it’s difficult to think about too much of something being the wrong thing.

Rooney writes about this excess head on. An excess of feeling, of loving and mourning, and an excess that is somehow never too much. Rooney’s girls (Connell Waldron included in that) don’t necessarily make good decisions. Or, don’t necessarily make the right decisions. But it never matters.

“To love is to be radically poor in control, and, for Rooney’s characters, humility can tip into humiliation, even masochism,” wrote Lauren Collins for The New Yorker.

Rooney’s characters don a perpetually-quivering lip. Hollow, indeterminate faces that somehow can never quite get away from one another no matter how hard any of them try.

One of the most valuable facets literature has to offer is perspective, a total immersion of another mind and experience and identity. That being said, my love for “Normal People” is self-indulgent. I am the prototype of the girl that these books are written for. White and overly-emotional, eternal optimist in the scheme of things and aspirational English major.

Critics write off Rooney for a legitimate lack in characters of color, and for her alleged Marxist beliefs snaking themselves onto the page. There’s no hiding the fact that Rooney’s “normal people” are white, affluent and, yeah, irish.

But some fans are so quick to defend her work — to discard genuine criticisms as a women’s issue — that they end up giving Rooney more credit than where credit is due.

Rooney herself questions the importance of her own novels, whether her books about “small lives” and intimate relationships are saying anything politically.

“When you inhabit a time of enormous historic crises, and you’re concerned about it,” Rooney said in a New York Times interview. “How do you justify to yourself that the thing to which you’ve chosen to dedicate your life is making up fake people who have fake love affairs with each other?”

Joan Didion once wrote that “we tell ourselves stories in order to live,” and if that’s true then Sally Rooney is life support for much of the world. It’s the triviality and mundanity, the subtlety of it all, that has turned Rooney into a bedside table comfort.