While discussing a mutually disliked class with a friend a few days ago, I caught myself nonchalantly asserting, “I’m just going to do the bare minimum to get an A.” The phrase made me question how there was such a thing as doing the “bare minimum” to get a grade that supposedly signified exceptional performance. The thing is, in today’s school climate, the level of performance one must maintain to receive an A in the majority of classes isn’t exceptionally high.

The answer to why largely lies in grade inflation, the general increase in students’ grades over time even as learning standards do not increase accordingly. The National Assessment of Education Progress recorded a trend of growth in the average GPA of high school students between 2020 and 2022 even as they found steady declines in reading, math and history achievement. Using another metric, standardized testing, shows us much of the same results. Average high school GPAs rose from 3.27 to 3.38 from 1998 to 2016, while average SAT scores fell from 1026 to 1002. The New York Times found that the ACT scores among the class of 2023 were the worst in over thirty years. It’s not just in the heads of the parents lecturing their high schoolers about how hard it was “back in their day”—it really is getting easier to pass.

A predictable effect of many students’ bare minimum being lowered is that students feel less pressed to apply themselves in their classes, receiving the same grades with lower levels of effort. If you don’t need to push yourself for a good grade, why spend your time trying?

“[Grade inflation] definitely makes people try less, which is not the end of the world—I mean, school’s not for everyone—but then again it sort of bothers me when I’m trying so hard and someone’s not trying at all and we get the same grade,” said Summit senior Lilann Hammack. “We’re supposed to be actively using our minds and trying to work through these harder classes if we go for them, which we don’t have to, and I feel like students are learning less because they’re not trying as hard.”

However, grade inflation isn’t exactly a clean cut issue. Students push for As as a way to set themselves up for their futures, often also carrying pressure from parents along with their own ambitions. When I asked Physics and Physical Science teacher Stephen Platt whether he saw a higher percentage of students going into classes expecting an A in recent years, he pushed back against the negative connotation of my question and offered a different perspective.

“I wouldn’t say [getting an A] is necessarily an expectation so much as a fear of not getting one…You know, ‘how can I compete unless I get an A?’” said Platt, who compared the process of applying for colleges today to the Hunger Games. “I wouldn’t put as much of a negative tone on it, like they ‘expect’ that, so much as they fear not getting that. Ascribe a little less ill-intent on their part, or sense of entitlement.”

It isn’t as if students have nothing to fear. Since the introduction of the CommonApp, it’s only gotten easier for students to apply to multitudes of colleges all at once—forcing those schools, with an overwhelming increase in applicants, to crank up their standards for admission and drastically bump down their acceptance rates. The probable reason that grade inflation is more pronounced at higher income school districts where students are wealthier than average is because teachers are just as well aware of this as we students and our (occasionally overbearing) parents are: enforcing rigor in classes may come at the expense of students being able to attend the colleges they aim for.

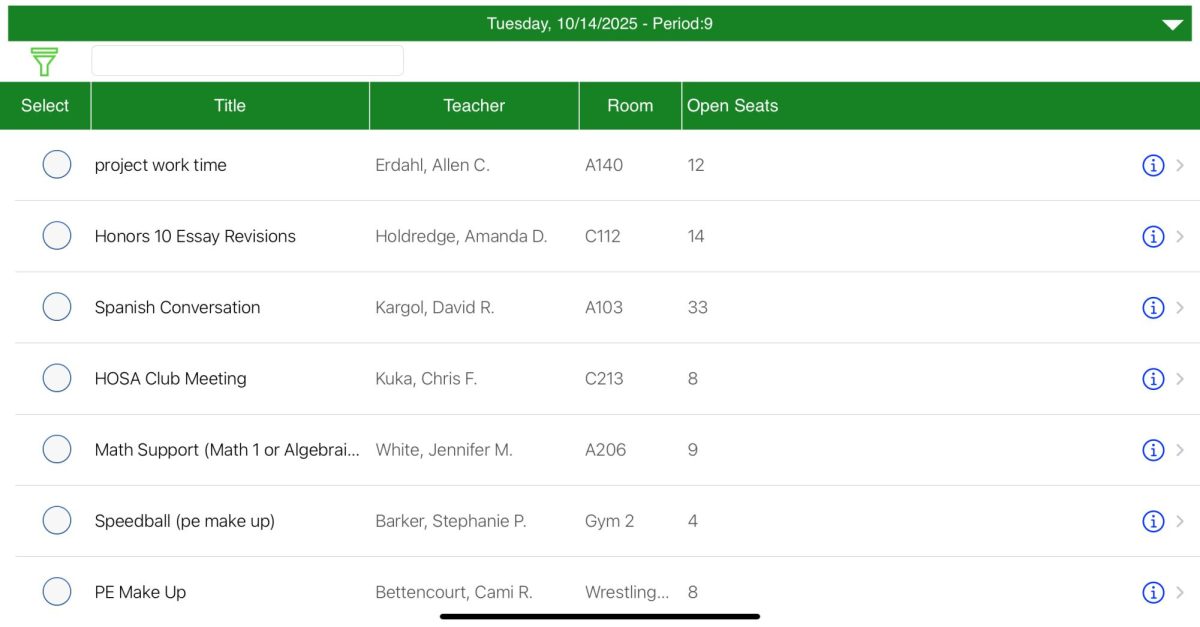

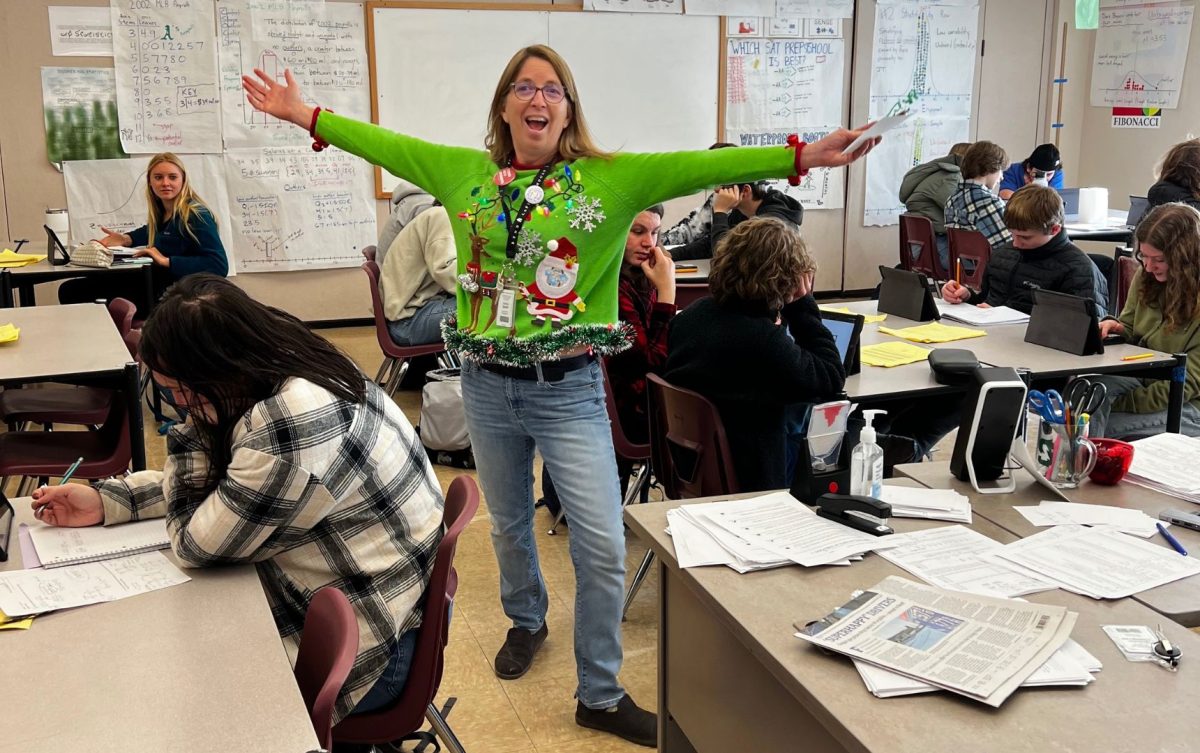

Summit AP and regular Literature and Composition teacher Amanda Holdrege stated that she did find herself doling out As on work that only earned a C or even D, but didn’t see a clear way to change the way she graded. Though she could try to assert more rigor in her advanced classes, she felt that there wasn’t a real way to walk the grade inflation process back once it had begun.

“It’s really hard with our population too, at Summit high school, with the students and the parents. There’s a lot of pressure on students and teachers to make As because so many of our students are college bound,” said Holdrege.

The pressure that teachers feel to help their students succeed in a very literal, immediate sense creates yet another steep obstacle to reducing grade inflation. As phrased by Platt, “if I’m not helping them then I’m hurting them.” However, while keeping college in mind, grade inflation isn’t exactly setting students up for success once they get there. The culture of the “bare minimum A” will end for most students when they graduate, and where will that leave us?

“I think that people need to take a step back and realize that especially in college, it’s gonna be so much harder,” said Summit senior Ryann Wilson, citing lack of study skills as one of the reasons why. “If you’re going to a school that has integrity and doesn’t grade inflate, you are set up to fail because of grade inflation…high school is supposed to prepare you for college and it’s not doing a great job right now.”

In the coming years, us college-bound students have a steep learning curve ahead of us as we discover that ‘exceptional’ is an exaggerated description of our work. Maybe it will show up in the form of multiple breakdowns over earning a C on a truly average essay, and then finally understanding the truth behind “Cs get degrees.” As for the high schools we’re leaving behind, is it possible to remake grades into truly accurate reflections of student performance? And even if it is, should we?

“Part of me, the part that grew up in the 70s and 80s, is more like, ‘yes, it should be more [like] only the people who deserve an A are getting As,’” said Holdrege. “But then this other part of me says, ‘why are we giving grades at all?’ Can we envision a world where students engage in content just for the pure joy of learning? That’s the ultimate goal.”