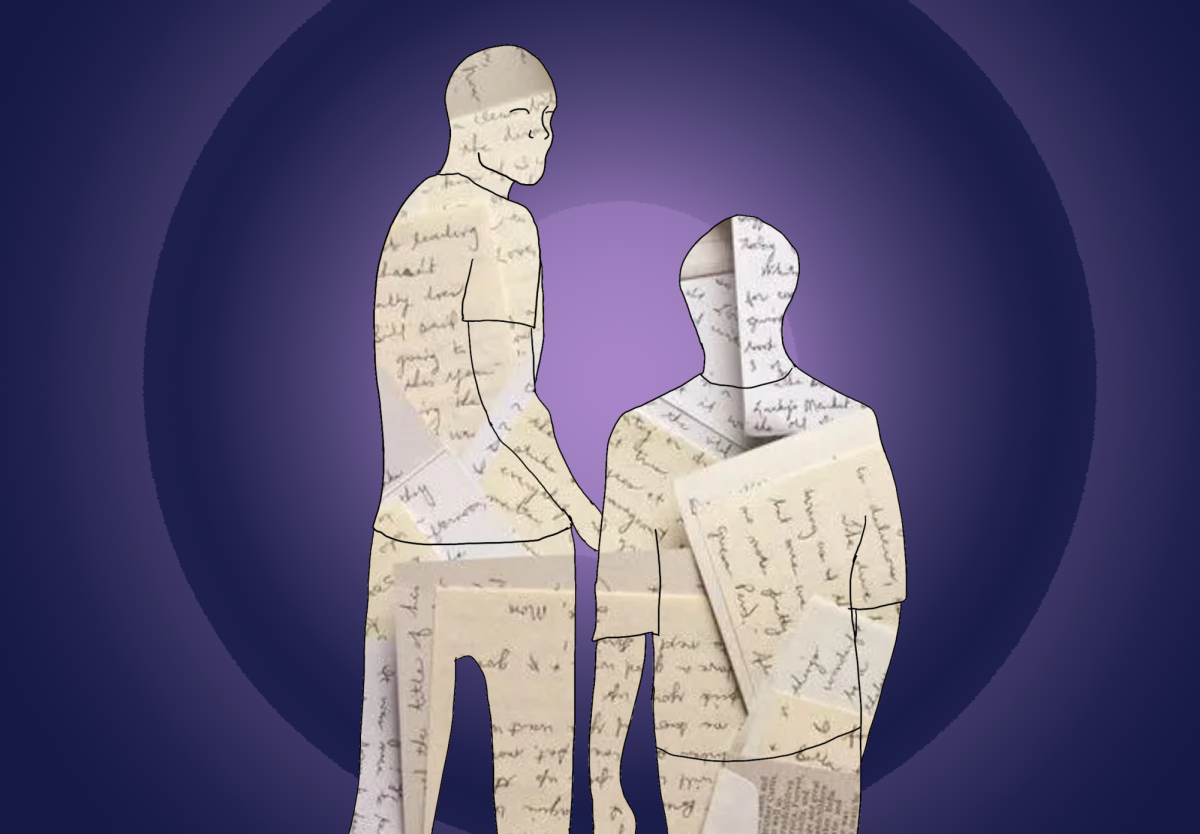

“Saltburn” is Shakespearean soirees. “Saltburn” is a pair of Juicy Couture sweatpants soaked in blood and vodka. And “Saltburn” is kaleidoscope-esque camerawork that when strung together creates an eerie and dewy-eyed landscape unlike (or like) anything you’ve seen before. But do any of these things actually mean something and hold true value?

Director Emerald Fennell, who is one of only five solo female screenwriters with an Academy Award for best original screenplay, is no stranger to controversy. This leaves her most recent film, “Saltburn,” labeled both a triumph and a let down by varying sides of the internet, keeping many torn on whether it did its job as a supposed “class commentary” or just basked in its own surface-level beauty. Shot on a 35mm camera, the vivid images of tortured beauty and brawn from an ending adolescence scorch into the retinas of viewers like images straight out of a dream. Yet if the viewer stopped for a moment, the question of “what the hell did I just watch?” would most likely come up.

“I personally really enjoyed the artistic beauty of ‘Saltburn,’ especially the incredible cinematography of the movie which was amplified by the intricacy of the costume and set design,” said Summit senior and Film Club President Andrew Schelling. “Yet I feel that Fennell’s creative vision for the story fell a little flat for me.”

However, despite its stunning color-drenched cinematographic work, “Saltburn,” at its core, has all the beauty of a piece of roadkill covered in day-old vomit. A different bodily fluid would make for a better analogy, but the use of that would only play into the most mindless impulses of Fennell’s catalog. While she can be seen as a modern day pioneer of elitist and vulgar auteurism, the director clearly leaned heavily on luxurious montages and nostalgia-filled needle drops here.

Additionally, “Saltburn’s” script relies on shock value and early 2000s nostalgia in lieu of diving deeper into the troubled characters.

“A lot of scenes felt like they were added just for the sake of being shocking, and it didn’t portray as interesting of a message on class as it may have hoped to,” Schelling said.

Some lines can feel off and as if they’ve come straight out of a cliche and embarrassingly edgy Y.A. book, yet the execution from a star-studded cast is nearly masterful. Each character is played with a fitting air of poise and unknowing entitlement, such as Rosamund Pike, who’s performance of “withering put-downs, extravagant living and self-proclaimed complete and utter horror of ugliness” (as described by Vogue) are a delightful sight to be seen. But of course the selling point for many was Jacob Elordi. The idea of the HBO heartthrob, sporting an eyebrow piercing at that, on the big screen surely sent shockwaves across the internet. And Elordi did stun, impossibly charismatic and kind, but arrogant, as the viewer can never completely tell if he really is this compassionate or is simply putting on an act to boost his ego.

In turn, parts of the film’s characters and plot earned its comparisons to Evelyn Waugh’s 1945 novel “Brideshead Revisited,” with The New Yorker calling it “a Brideshead for the Incel Age.” But where “Brideshead” shares a ruinous romanticism in its ill-fated elites, “Saltburn” holds only carnality. And how sickening it is to view such shallow, spiritually lifeless hunger.

Still, Fennell is attempting to make art that feels completely unique in its chaotic, bold and grotesque nature, and rooting for her only feels natural. Perhaps because of all this, films like “Saltburn” are an important art of our time. In an attempt to be shimmeringly enigmatic, they are only glaringly insubstantial.