*spoilers follow, along with stellar intellectual insight*

“Strain a girl to her absolute limits with wanting you, and she won’t have space in her life for wanting anything else.”

– Rax King, independent culture critic on “Priscilla”

Americana deity, a figure of winged eye makeup and dark hair piled high in a beehive above her head, Priscilla Presley’s silhouette is nearly as recognizable as that of her bedazzled-jumpsuit-adorned former husband, Elvis Presley. Just nearly.

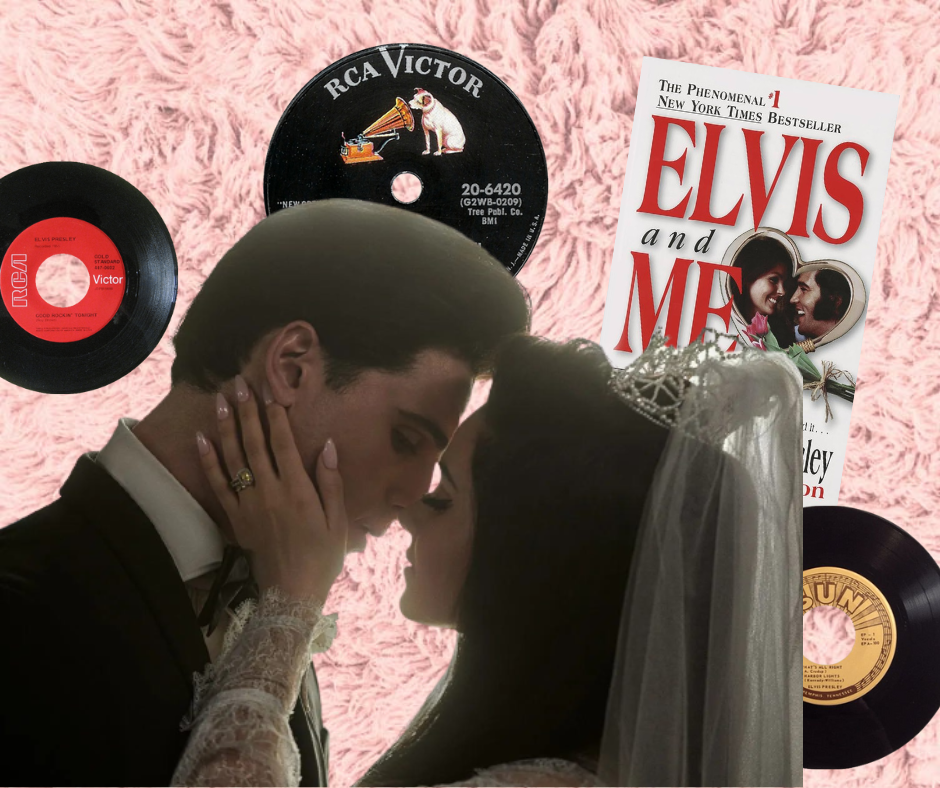

“Priscilla,” an almost auto-biopic based on Priscilla Presley’s 1985 memoir “Elvis and Me,” hit theaters October 27, starring Euphoria red-flag heartthrob Jacob Elordi as Elvis and Cailee Spaeny as Priscilla herself. Directed by girl of girls and daughter of “Godfather” director Francis Ford Coppola, Sophia Coppola, “Priscilla” matches previous projects—powdery-pink cult favorites like “The Virgin Suicides” and “Marie Antoinette”—and reflects favorite themes, too. Girls lost in the trap and turmoil of their circumstances, and clawing their way out.

“Priscilla” comes a little over a year after Baz Luhrmann’s 2022 film “Elvis,” starring a method-acting Austin Butler as Mr. Presley and examining rise to fame. But “Elvis” was not all about Priscilla, just as “Priscilla” is not all about Elvis.

We meet Priscilla in 1959 and follow her through the early 70s—and the entirety of her relationship with Elvis Presley. A naive army brat stuck with her father stationed in Germany, she’s working on freshman year homework at a diner counter when she’s approached by a friend of Elvis and invited to attend one of his parties at the tender age of 14. The parties turn into courtship, which turns into a long-distance situationship, which turns into Priscilla moving into Graceland when she’s seventeen (and her parents somehow being alright with that).

We watch as she prunes herself into Elvis’ ideal woman via a trademark Coppola coming-of-age makeover montage—“black hair, and more eye makeup,” the ready-made, rockstar-selected look that turned into her legacy. And at the end of it all she finds herself in California, estranged from her husband and practicing taekwondo, beginning her next journey in finally finding herself.

Visually, Coppola’s “Priscilla” is aesthetic perfection. Graceland is a dreamlike replication of the real thing, plushy carpets and cream-colored textiles that forge an austere stillness around Priscilla when she’s placed in this house she cannot leave. She’s left alone to wander and wait for Elvis to get home and notice her, instructed to be there when he calls—if he ever does. That’s the majority of “Priscilla.” The waiting. The pruning. The total loss of autonomy. In one scene when Elvis and his gang of goons take her shopping, he instructs that no, she can’t wear brown because it reminds him of the army. No patterns because it distracts from her face. She looks nice in blue. He likes her in blue. She’s allowed to wear blue.

Denied music rights by Elvis Presley Enterprises, Coppola took to the eras to build a soundtrack for “Priscilla.” Curated by Coppola’s husband and indie artist himself, Thomas Mars, and music supervisor Randall Poster, the movie sonically juxtaposes classics of the 1960s with 90s deep cuts like Spectrum’s “How You Satisfy Me” and scattered 80s hits. The Righteous Brothers, to The Ramones and Tommy Jones & The Shondells, and back to Brenda Lee.

A multitude of gospel songs on the track call back to Elvis’ deeply Christian identity, featured throughout the film and felt deeply by Priscilla, too. Felt both via his not wanting to have sex with her and in the physical porcelain figure of Jesus commanding the corner of his bedroom that they share.

There are moments of absolute absurdity that sent a theater giggling—Elvis’s organized book burning after his manager Colonel Parker tells him his newfound interest in philosophy has become a distraction from his career—and moments to really truly fear for the girl.

Elvis abused prescription pills throughout his life and career, and coupled with anger issues already there led to a chair thrown at Priscilla for voicing her opinion on a song. However—aside from those outbursts—the most striking thing about “Pirscilla” is that Elvis is not overtly the villain. He isn’t depicted as a sort of larger-than-life, child-molesting monster who stole a girl away from her family. He’s stripped from the pomp the public has known and seen—the media narrative still being fed into today—but is condemned to a man who somehow garners slivered sympathy. For a moment, “Priscilla” is a love story. A wolf in sheep’s clothing. But it’s in the next instant, in the ultimate ever-anticipated flash of anger, that he’s shown for what he was. A man who lured and trapped and hurt.

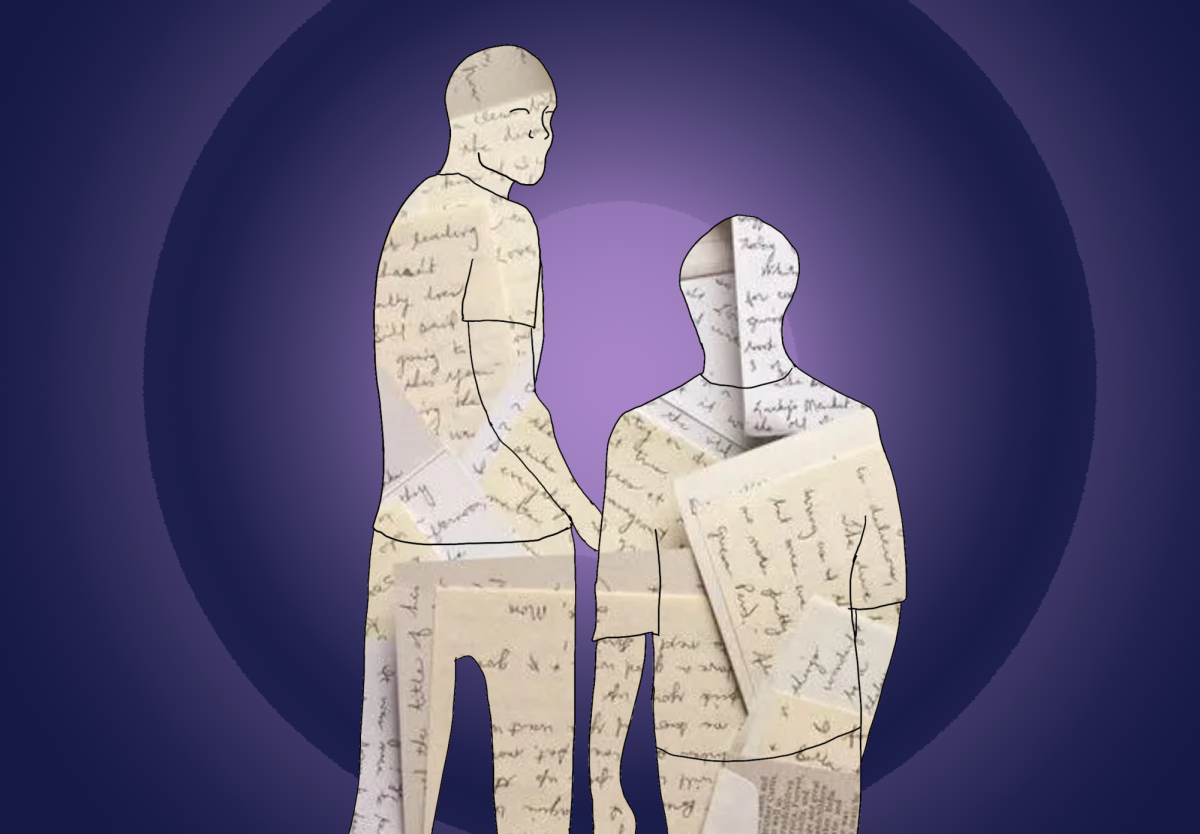

Throughout her films, Sofia Coppola selects a very specific kind of woman as both muse and perspective, and at many points “Priscilla” stops being about the former wife of a now-deceased celebrity figure and turns into a study on any young woman losing herself, and hurting, and attempting to find herself again.

“I rarely saw teenage girls depicted in a way that I felt was relatable and kind of true to that experience for me,” Coppola said in an interview with NPR. “I always like stories about transformation—and that’s such an extreme time of transformation.”

“Priscilla” reflects many girls’ first real relationships, and the darkness that can exist within that. How easy it is to lose yourself to the draw of being desired, and the isolation that comes when that desire dissipates. The only difference is that Priscilla’s isn’t a high school love affair to last all of five months and end awkward enough but to be forgotten about eventually. This was nearly fifteen years of her life devoted to a poisoned puppy love.

Despite that, there is never a point in the film that Priscilla reserves to no longer love Elvis. She never turns bitter, bent on vengeance. In the final scene, Dolly Parton’s “I Will Always Love You” fades out as Priscilla drives herself through the gates of Graceland for the last time after collecting her things—the same song that the real Evlis fought (and lost) publishing rights for and sang to the real Prriscilla as they left the courtroom hand-in-hand after finalizing their divorce in 1973. “Priscilla” ends on a resounding question mark, and credits roll with a jerk, because here is the beginning of a woman’s story. A story that’s yet to end.