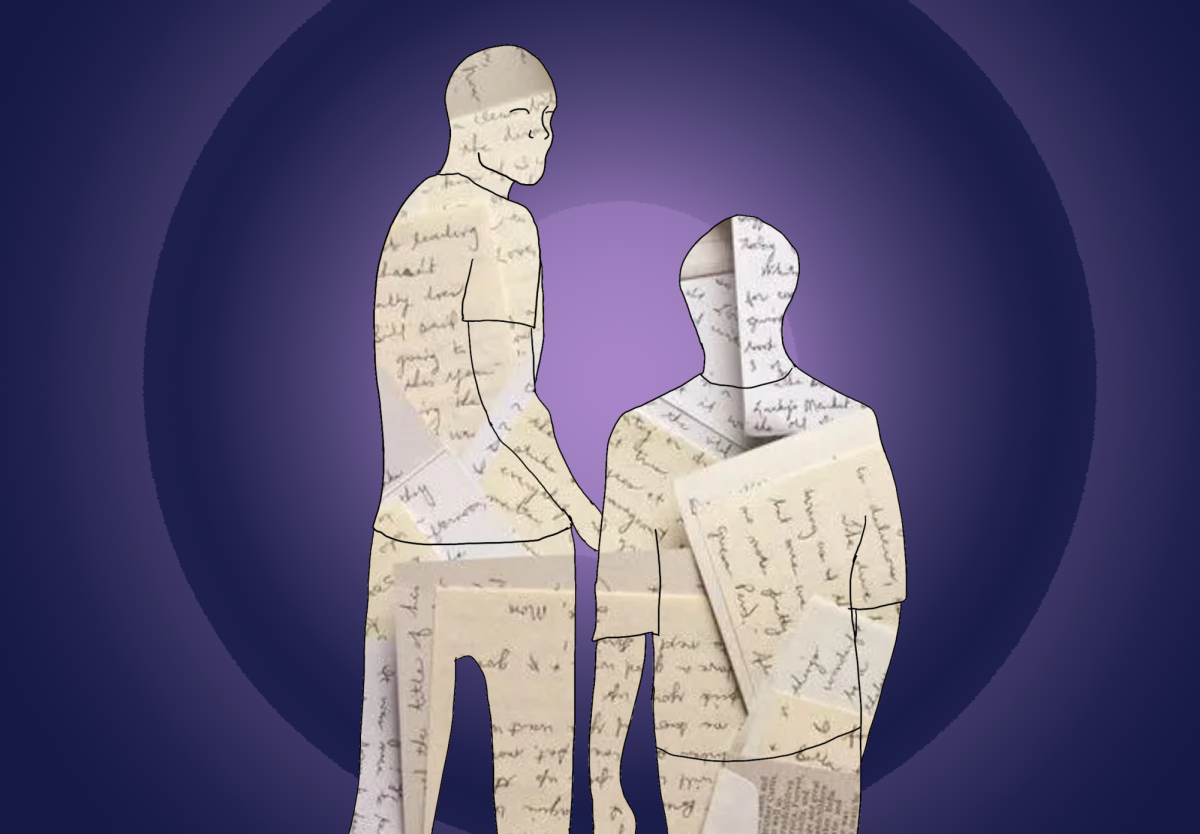

One of the most important aspects of history is how the story is told. Among the most highly debated controversies today, the U.S. History curriculum is one of the most passionate. For a typical high school student, their mandated classes about U.S. History might be the only time they ever learn about the history of their own country—and the question arises: what do school districts teach their youth, and what do they leave out?

The topic of history can be historically painful, as popular narratives like Christopher Columbus finding America survive in our education system today. Although the Department of Education is in charge of making sure America’s students are getting the schooling they deserve, it’s up to the states to decide their individualized standards for a history curriculum. And yet, the American population still bickers over the best way to do it.

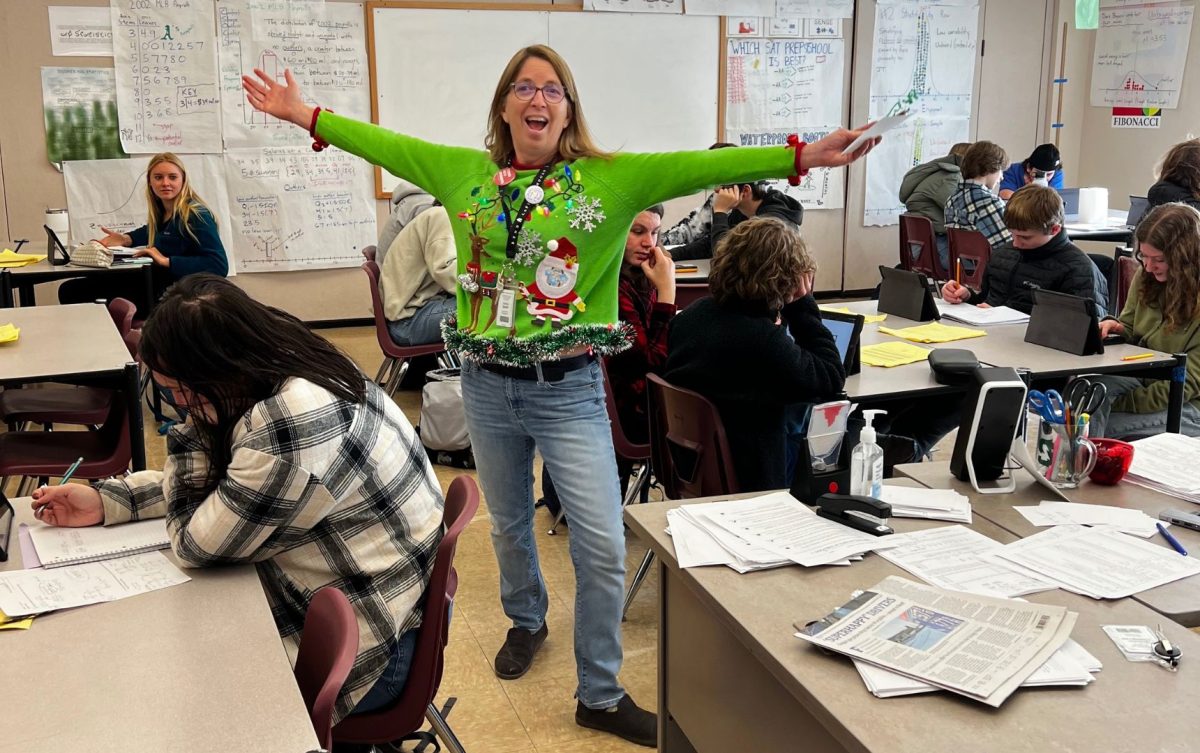

“It is really interesting how your experience with U.S. history could look vastly different depending on where you’re going to school,” said Summit teacher Marni Spitz. “I think that’s even true even within the state of Oregon—we’re really lucky. At Summit, teachers get a lot of curricular independence and ownership.”

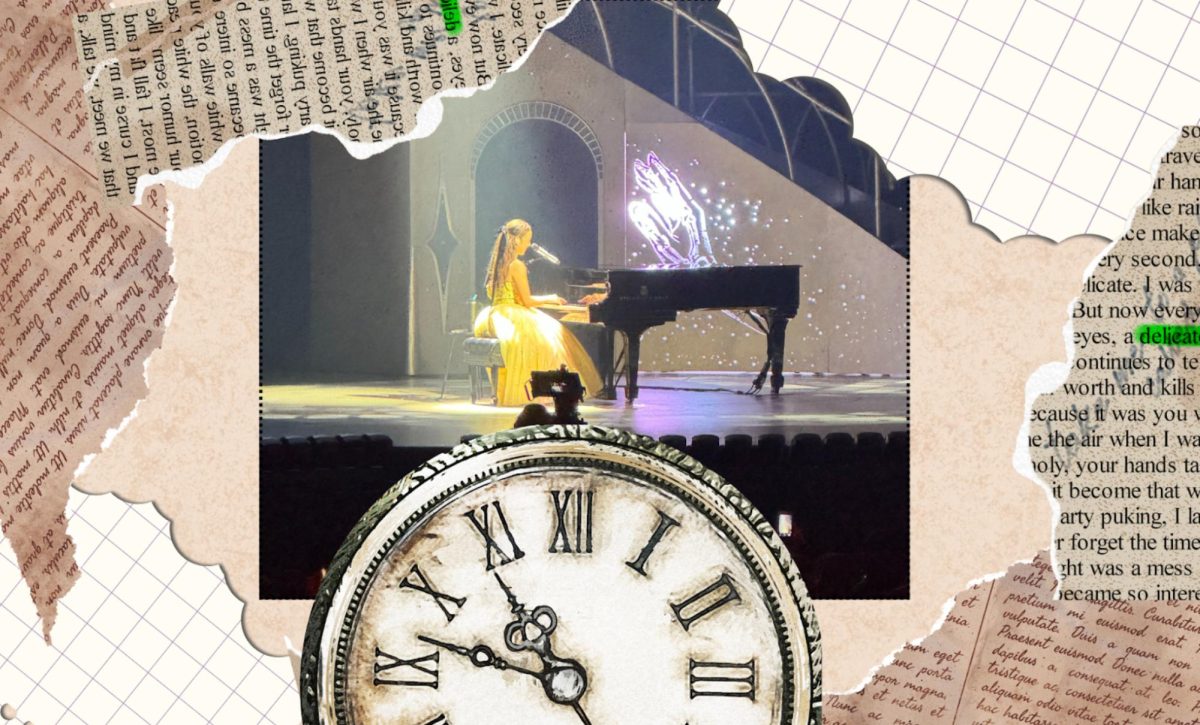

Spitz teaches A.P. Government, U.S. History and the only ethnic studies class offered at Summit. History teacher Sarah Warsaw and Spitz collaborated to come up with the curriculum for U.S. History, which is a year-long course that is required to graduate. The only alternative to this class is College Board’s AP U.S. History, affectionately known as “APUSH,” which uses the same curriculum nationwide.

According to Education Week, guidelines for history classes are developed by state committees that are updated every seven to 10 years, with the state board of education as the final say in what goes into the curriculum. Therefore: 50 states with 50 different history classes.

With Oregon being a steady blue state, bordered by highly progressive California, it’s not surprising to find an overlap between history and ethnic studies classes. Whereas other states have a different outlook on U.S. History classes, in states recently cracking down on ethnic studies, such as Arizona’s 2010 ban on ethnic studies and the subsequent turnover in 2017, their approach to a history class has been largely traditional and patriotic.

Even Oregon—while being largely liberal—has diminished the importance of critical history lessons being taught in public schools. Charles F. Horne, a college professor who penned an inaccurate, racist version of American history, was commended by Oregon’s governor, Walter Pierce. Horne’s book, “The Story of Our American People,” was an earnest, unwavering dedication to American nationalism. According to The Washington Post, Pierce, who was endorsed by the Klu Klux Klan during his time as governor, called the book “‘the finest history of early America that we have ever had.’”

While a traditional U.S. history class revolves around the change-makers that inspired America’s dream (think the admiration of the Founding Fathers), newer courses focus on an introspective lens instead.

“The way that we’ve done it is really to think about big themes that we would like students to be thinking about all year that don’t have a definitive answer,” said Spitz. Some of those big themes are structured as questions such as: what does it mean to be an American? What are the founding ideals, and what is the American dream? “[By] rooting units in those big picture kinds of questions that don’t have a finite or definitive answer, they open up [the] conversation.”

Instead of trying to rationalize American mistakes, Spitz and Warsaw have developed an opportunity for students to try and critically analyze the narratives the U.S. is known for. In order to do that, many lessons in Summit’s U.S. History overlap with ethnic studies, which goes more in-depth on minority issues.

“When I was teaching ethnic studies last year, some kids were kind of immature about that sort of stuff,” said Tyler Crowder, the long-term sub for Warsaw. Having subbed for two years in Warsaw’s place, Crowder has taught everything from U.S. History to AP Human Geography.

“After certain subjects, they were like, ‘Oh my god, I’ve never thought about that,’” said Crowder. “I showed them examples of the civil rights movement that we could only briefly cover in our U.S. History classroom, covered more in-depth. If you look at other school districts, even in Oregon, there’s some stuff we can teach, but other school districts can’t, because they don’t want kids learning about it.”

While ethnic studies is part of U.S. History, it’s not all of it. The sheer amount of content required to be covered in a general history course means that ethnic studies can spend more time focusing on eras like the Civil Rights movement and gay rights movement, using case studies and documentaries to put together a more nuanced story of history.

“Embracing ourselves as Americans and our story,” said Spitz, “it includes all the things we’ve done amazing, and it also includes all the things that aren’t amazing, and I think that’s really important for students to grapple with. How do we reconcile this place that is so beautiful, and it’s founded on these really beautiful ideals, but we had institutionalized slavery for 236 years?”

History in and of itself is a lesson taught to ensure that the future doesn’t repeat the past. According to Oregon state standards, set to run until 2025, classes are required to critically examine and discuss the impacts marginalized groups have had on American culture. Learning about events from multiple perspectives, such as Japanese incarceration camps during World War 2, is also highly encouraged.

“When we create a more just world, it’s not just for the people who are being oppressed or marginalized or underrepresented,” said Spitz. “It benefits everybody when we try to combat these things. And so it’s especially important in communities where they are mostly a dominant culture. It’s not any less important to have an ethnic studies class for a predominantly white school than it is at a school with predominantly students of color.”

In a district like Bend La-Pine, finding these perspectives can be difficult due to Oregon’s demographics. Buffering the curriculum with resources from historians, essays and case studies helps students understand the often double-sided story of American history.

“I think it’s hard for kids who have grown up here and haven’t really experienced the differences people have based on skin color, race or ethnicity,” said Crowder. “But it helps them. Using ethnic studies, AP Human Geography, psychology, world religions—the more social side of the social studies department—helps kids connect with things that they just haven’t experienced in their life in the first place. And it helps them empathize with those minority groups.”

With fifty different standards for history, it’s not unreasonable to expect vastly different views on America’s past from a population in the same country. With a revised, newer curriculum, the intent to change our future by reflecting on our past is all that’s intended—through the good, the bad and the ugly.

Barbara • Nov 18, 2023 at 5:35 pm

How about we teach the broad perspective first, get kids to understand just what our founding fathers (and I do say ‘our’ because we are citizens of America) fought and died for? What was it like before freedom from tyranny,what it was like after, what is a ‘republic’ and why has so much of the world wanted to emulate our Constitution? THEN talk about slavery, the history of slavery around the world and then history of American slavery. Can we agree to focus on the majors BEFORE we focus on the minors (not solely minorities)? Big picture first, people. What ding bat thinks history is about ‘getting students to think about questions all year that have no definitive answers’? That’s for college level, not pre-teen and teenagers. Duh