No One Cares About Smarter Balanced Testing

And why should they?

Corralled into the small gym by word of mouth, I spent fifth period last week guessing on a twenty-question multiple choice math test while “Doses & Mimosas” and 2000s hype-beast remixes leaked through the walls of the weights room. I had spent that morning in my English class—dwindled down to the five students who’d forgotten to opt out—clicking through questions until I got enough wrong to not be fed any more.I’d done the same the previous day on the science portion, opting to forgo even reading the questions after a certain point.

Smarter balanced testing remains, to me, an utter mystery. An annual assessment that I never saw any sort of feedback from, but that I nonetheless would put as much of myself into, as any other test that did actually contribute to a grade. I packed headphones the night before, I bought gum for the occasion and I took the time in providing thoughtful answers. That effort was expected of me, third grade through eighth, and I never questioned it.

As smarter balanced testing has returned post-pandemic, there is an overwhelming refusal to take it seriously. But how can students be expected to try on a test that teachers and administrators continually seem to stress the lack of importance in?

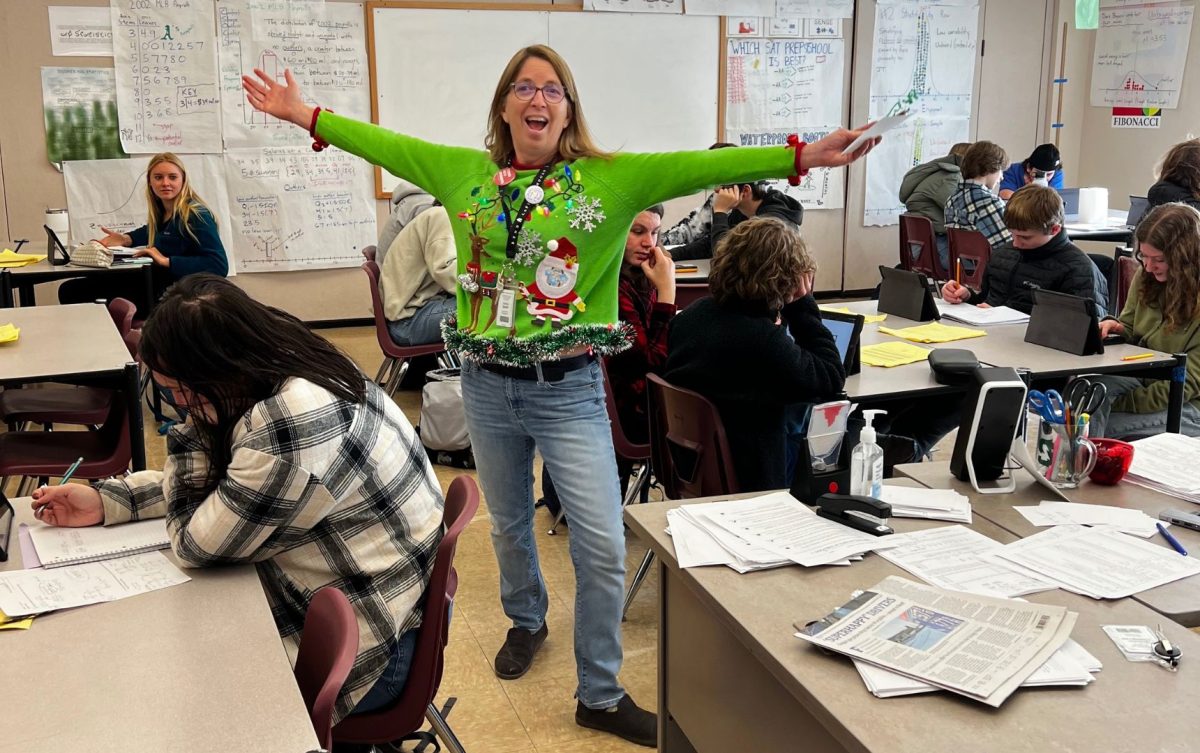

“I think that there are more authentic ways to see where students are,” said Summit English teacher Kelsie Layana. “Because we don’t tell our students that this is an important test, they don’t see the importance in it.”

Disgruntled sighs accompany instructions to download the secure test browser onto our iPads. Nods and winks as students file down to the front office to pick up their own copies of opt-out forms to forge signatures on. Muddled answers to the question everyone keeps asking: “why?”

Rationale varies. There’s a lack of consensus whether the SBAC is a reflection of the school, of how well teachers are doing their jobs, or just how dumb the upcoming senior class is.

Smarter balanced testing has become laughable. Ritualistic. One word answers and emoji middle fingers can’t come as a surprise to teachers, because there’s really no greater effort expected.

It’s a similar phenomenon to Bend-La Pine’s annual district assessment—the ill-famed, eye-roll-inducing CDA. Stressed as another pointless endeavor, some of this year’s essays can’t even scrape by with alloted participation points. An apparent reflection of perceived priority, students are designating their efforts elsewhere.

“Students know teachers’ hearts aren’t into it,” Layana said.

Most juniors are balancing finals throughout classes—the end-of-year essays and presentations and exams. I sped through the SBAC science portion in order to start work on a final project for AP Biology, and most other students did the same. State testing is treated as an inconvenience, if anything.

The simple fact is that no student is going to devote themselves to an assessment that does not translate to a tangible letter grade or an additional bullet point in a college application. Smarter balanced testing contributes an inaccurate reflection of schools and education, but a complete reflection of administrative attitudes impacting students’ levels of effort.