Favoritism in the Classroom

In the brief daily hallway chats between Summit students on their way to their next classes, it is easy to pick up on grumbling about certain projects or teaching styles. However, the complaint that has been sticking out with increasing frequency these days is one about teacher favoritism.

Allowing students to have an extension on an assignment, permission to leave the classroom, change their seats, or do a project in an alternate way is far from a bad thing—as long as opportunities to earn these privileges are equally afforded to all students.

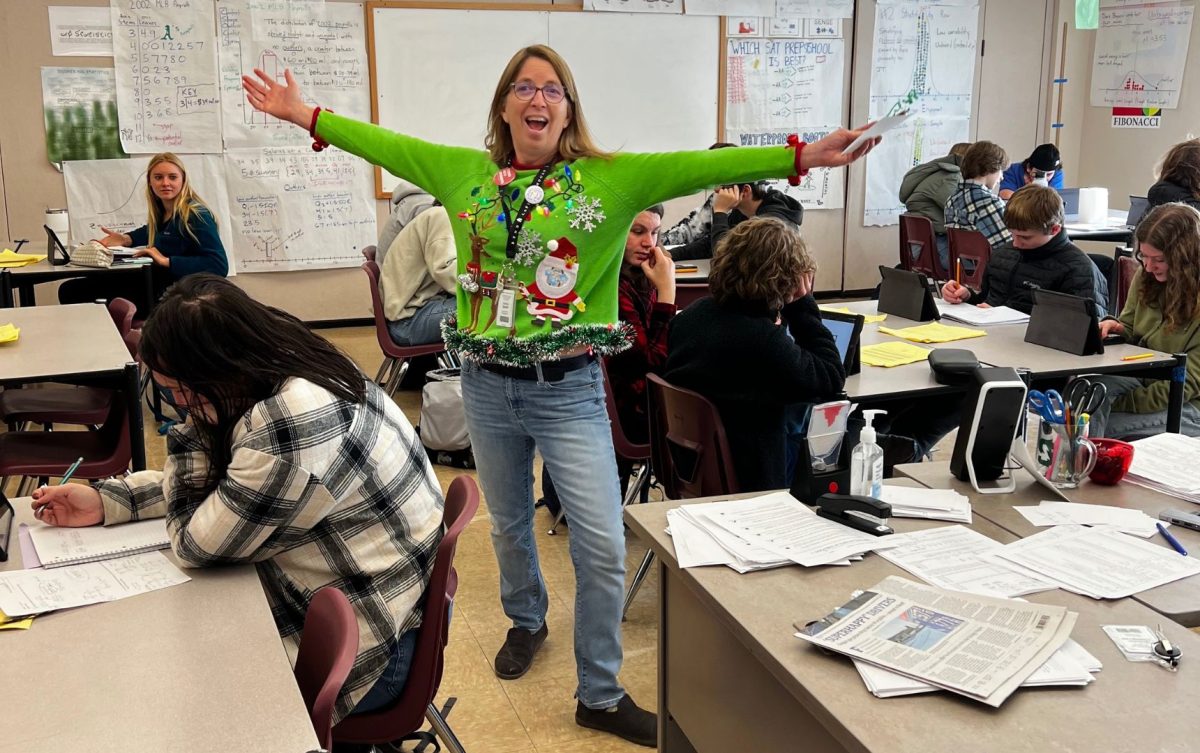

Put simply, favoritism is unfair support shown to certain individuals by a person in authority. Emphasis on the “unfair” part. Giving special privileges to specific students that not all students are offered isn’t always a bad thing, and is sometimes necessary. People with learning disabilities are afforded extra time and other benefits, and in such cases, it is obvious why “fair” doesn’t always mean giving the exact same treatment to everyone regardless of circumstance. Similarly, sometimes teachers will give and take away privileges based on demonstrated trustworthiness (such as banning some students from working in the hall if they have proven to skip class when given this opportunity), which wouldn’t factor into the favoritism discussion. Freshman biology teacher Krista Brines defined favoritism as “developing a relationship that excludes others.”

Teens at Summit don’t point fingers blindly. It’s clear in many classrooms that certain students get special treatment that has little to do with outstanding circumstances or even academic merit.

While researching, I found multiple studies unsurprisingly affirming that charming, socially skilled students had a higher likelihood of becoming a teacher’s favorite.

This is where we get the stereotype of the “popular kids” who the teachers adore despite causing disturbances in class. Indeed, the most striking commonality whenever I inquired about the types of students that benefit most from favoritism was the word “popular.” Also commonly mentioned were the words athletic, social, rich, and confident.

“Those people who are more confident, have a bunch of friends, everyone knows them—teachers see that they’re the popular kids and they want to get on their good side so that the kids can spread the word that they’re a cool teacher or something,” said Rose Brandt, a Summit sophomore.

One teacher corroborated that unprofessional student-teacher relationships can stem from something as simple as the teacher’s desire to be seen as cool, to fit in somewhere in the high school social hierarchy.

The most interesting data I found online was from a 2008 Turkish study that found that students receive more special attention when they came from a similar background to the teachers themselves. Multiple teachers confirmed that students are more likely to benefit from favoritism if the teacher sees themselves in the student. More similarities may create a subconscious affinity for certain students that can result in biased treatment.

This biased treatment isn’t hard to pick out either. The only thing more shocking than watching students in my classes try to flirt their way into better grades is watching it occasionally work—and I’m not the only one noticing that sucking up to teachers can get you better treatment. As soon as one person successfully brown noses themselves into a teacher’s favor, others learn what works and are quick to imitate it. A certain math teacher accepts gifts, the history teacher appreciates compliments, the English teacher rewards students that consistently inquire about their personal life.

So yes, these “teachers’ pets” know what they’re doing. They’ll freely admit it when chatting amongst themselves. And honestly, who can blame them? The structure of today’s school system has made grades the top priority of education. With college admissions (along with merit aid), personal goals, and parental expectations on the line, all that a lot of students care about at the end of the day is getting the A. Hell, even driving insurance gets discounted if your grades are good.

Really, being a brown noser can’t cause that much shame when it can save you money and effort. Recognizing the ways you can put yourself ahead (even by groveling) and using all of the tools at your disposal is a skill in and of itself.

However, favoritism can have negative effects on the learning of all students in the classroom—both those who receive special treatment and those who do not. As Brandt pointed out, this process harms both groups. The rest of the class can end up not even wanting to try because the teacher doesn’t like them anyway, and a favorite may not pay as close attention because the teacher does like them and they’ll get a good grade regardless. Addie Onstead, a junior, mentioned that she feels less inclined to try her best in classroom environments that feel unfair. She just sits down and does her work and then “gets out.”

“I’m sure it can drain a student if they know that they’re being treated unfairly, especially by their teacher, someone they’re supposed to look up to. If they don’t feel as if they’re being cared for they might not put care into their studies,” said Luca DiGiulio, a junior.

To lessen the negative effects of favoritism in the classroom, it is most important to start by keeping personal bias out of grading. Multiple teachers confirmed that their grading followed specific rubrics—both to show the student the areas they can improve on and keep the teacher accountable for grading fairly. Another stated that she sometimes will grade with name labels turned off. Offering revisions and resubmissions for projects with more subjective grading (such as essays) was another proposed solution, so if students felt like they deserved a better grade they had the opportunity to make it up. In regard to special privileges, science teacher Chris Kuka stated that he wouldn’t make exceptions to his usual rules without sufficient reason.

“If I make any sort of adjustment to what I expect, I need some rationale as to why from the student,” said Kuka.

When I asked the question of how teachers should keep bias out of their classrooms, I got quite different responses. Teachers tended to answer with specific policies they enacted to make sure their grading and issuing of special privileges was fair, while students offered suggestions on how to foster an inclusive classroom environment.

“I think [teachers] need to act more inclusive towards and make better connections to the kids that aren’t pushing towards getting their attention,” said Summit junior Addie Onstead. “They definitely give all their attention to the kids that want their attention, but some of the kids that just sit there and do their work—there’s not a lot of attention put towards them.”

Having positive relationships with teachers is beneficial for both student well-being and engagement in class, but it is important to ensure that these connections do not land some students with greater opportunities than others. To ensure a fair and enjoyable learning experience for all students, a combination of the more practical solutions about grading and the general recommendations about treating students equally should both be considered.

Features Editor Jesse Radzik is just like your average grandmother, if said grandmother managed to avoid bone degeneration enough to play varsity tennis. She greatly enjoys reading in little nooks, doddering...

Sharon Goodman • May 24, 2023 at 6:17 pm

Very thought provoking and quietly worrying….how can I give of my best, without having to try and influence my teacher first, in some way, to take notice and appreciate my capabilities and determination.