What Happened to Our Summit Furries?

Are furries truly extinct, or have they simply gone underground?

Deep in the social recesses of the Summit communal sphere, furries are hiding from the spotlight. Furries, of the people-who-dress-like-animals fame, who—like many ostracized fandoms—have made their comeback into popular culture as the go-to butt of a joke. (Infamous examples include the fandoms of “[Boku no] Hero Academia,” “Steven Universe” and “Five Nights at Freddy’s.”)

This disgust hasn’t left public sentiment—in fact, in March 2022, Bruce Bostelman, a Nebraska State Senator, apologized for inciting a debunked rumor that schools were providing litter boxes for students who self-identified as cats. In fact, even the most open-minded of my interviewees cringed when they heard the word “furries.”

Furries, according to popular culture, are people who wear fursuits, draw anthropomorphic art and are attracted to animals, spawning on Twitter and Discord. In 2019, a Summit Pinnacle article detailed furries out-and-about on campus, a startling contrast to our community four years later—in which most people don’t know there’s secret furries attending Summit. But reality is never that simple, and I was determined to find the truth.

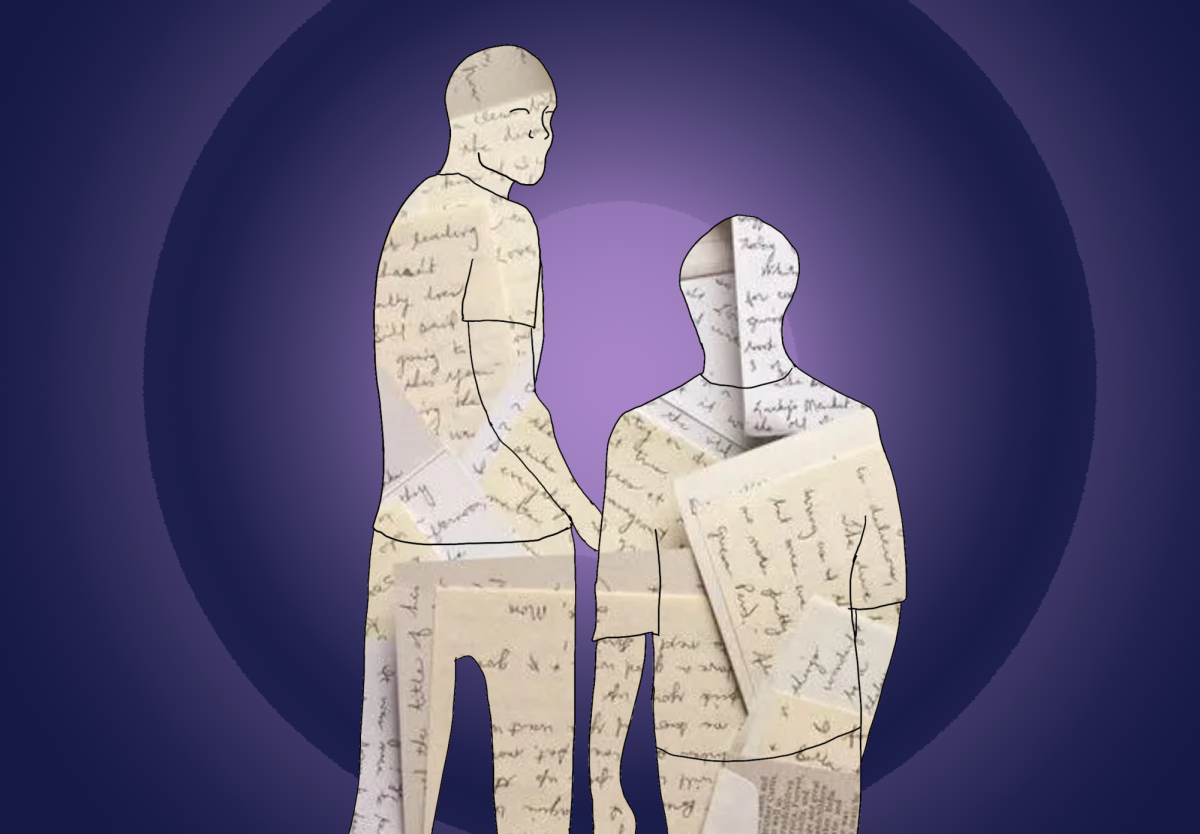

I started my journey with one of the only connections I had to this intangible world: an ex-furry, who I’ll refer to with her fursona name, “Eliza.” A fursona, the basic building block of a furry identity, is an identity or a character created by an individual as an anthropomorphic animal, usually drawn. None of the furries interviewed wanted their real names included in the story, for fear of harassment.

A depressed, white fox with gray patterns, black hair covering one eye and a magical amulet hanging around her neck, Eliza was the ideal fursona for an eight-year-old interested in “Warrior Cats.” Eliza herself is somewhat of a historian in all things pop culture; name a fandom, and she’s probably been a part of it. She’s one of those rare people who retain all the information about one completely obscure thing—the thing that’ll save you from ending up as a victim in a crappy “Saw” movie spinoff.

“After the… uh… Furry Vs. Gamer war—“ said Eliza, when I asked her about the disappearance of furries nationwide. “I have to bring that up, I just have to.“

She went on to explain a TikTok feud in 2018 that pitted united Furries and Gamers against each other, and surmised that to be the cause of the mass rejection of fur-culture in society today. It had ultimately ended in a truce, and the pivotal moments were recorded on WikiFandom—after that, furries seemed to retreat from the popular social sphere, as backlash began spiraling out of control. However, the problem seemed much deeper than that—not just a fake online war, but a deep societal shift in how accepting we are towards anyone “different.”

Eliza herself retired her fursona years ago, citing her exit as a natural conclusion to that part of her life. However, even though she’s no longer a furry, she wanted her anonymity upheld, due to the fear of being outed as an ex-furry.

“As time went on, I guess I sort of found other interests,” said Eliza. “And with the rise of seeing different people in the community, and others in the public’s reactions to that was just kind of… it steers you away from it.”

Eliza’s experience is far from unique: in fact, all the furries I interviewed seemed to have gone through the same sort of bullying, either online, or in person.

“Online, I have been sent death threats just for drawing anthro (anthropomorphic) characters,” said Harper, whose fursona is a spotted and striped hyena. “I’ve had family members cut ties with me over it, and in younger years of my life, did lose friends over it. It was easier to come out as queer than it was to say, ‘Oh by the way, I draw cartoon animals.’”

An anonymous student also described his experiences with people barking, walking into him and his friends or pulling the keychains off of his backpack. The reasonable way to treat furries, nowadays, is not outright violence, but rather an ostracization that seeps into every facet of daily life, whether it be walking to class, or just getting lunch.

“I wouldn’t be physically hurt, but it would just be, nowadays, it’s all just passive,” said Tanny, whose fursona is a yellow fox. ”It’s all condescending and passive-aggressive.” His experiences included being barked, honked and yelled at on the streets for wearing a fursuit in Downtown Bend. “You have that popular kid talking to you, and you know that they don’t care. And they’re trying to get something out of you just so that they can gossip about you.”

For many of these teenagers, being a furry can be isolating. What turned Eliza away from the fandom also discourages others from joining: the guarantee that you will never be completely accepted in a public space.

“I mean, growing up, or just in general, a lot of people think furries are really weird, and like, avoid them, or bully them, or make fun of them,” said Eliza. Although she isn’t a furry anymore, some of her friends who identify as furries are bullied every day for their identities. Eliza is too, just by association.

But why is this happening? Why do we harass furries at the scale that we do?

Many furries attributed the sheer scale of hatred to popular media that influenced an older generation. In 2003, CSI aired an episode named “Fur and Loathing,” which depicted furries as sexual deviants who enjoyed having intercourse in fursuits.

“That’s where the whole sex thing came from, cause [CSI] made fun of [furries], and faked it,” said Harper. “Our parents would watch that, and they’re adults, so they would think that, and younger kids think that, so just about all of the hate and all the misconceptions are rooted from that episode.”

Michael McNamara, a filmmaker who, at the time, was working on a documentary episode about furries, even said that the episode was a misrepresentation of the whole fandom.

“[Sexual deviancy] probably represents about two percent of fandom, but it’s the one obviously that the press always gleefully jumps on,” said McNamara in an interview with CinemaSpy. Greg Gaudio of The Virginian-Pilot also attested that one of the furry fandom attendees he interviewed said that the activities represented in the CSI episode “only involves a tiny percentage of furries, and is not something that’s part of the local scene.”

Misconceptions about the furry fandom like these; that they’re attracted to animals, that they use fursuits as a kink, or that they pretend to be animals, are just that—misconceptions.

“Furries do not engage sexually with animals, and furries do not think they are animals,” said Harper. “Those are the two most common insults that are thrown around that are just outright wrong. The furry community goes out of their way to hate on bestiality and zoophilia—it will never be welcome.”

Every furry I talked to wanted to clarify: attraction to animals, having sex inside of fursuits, and thinking themselves as animals just aren’t common behaviors for anyone in the furry community. (Thinking of yourself as an animal is a mentality widely equated to “therians,” or “Otherkins,” who believe they are animals in a human body.) In fact, most furries don’t even own fursuits, which can cost anywhere from a few hundred to thousands of dollars, depending on the scale and intricacy of the suit being commissioned.

When we think of furries, we often think of zoophiles instead—those with a disturbing, illegal attraction to animals. The only problem is, furries are often associated with it. Even though most of the furries I interviewed had online fursonas only, leaked identities could cause serious repercussions for them at school, or at home.

Zoophiles, while not considered part of the fandom, don’t stop young furries from getting misdirected hatred based on the assumption that they are attracted to animals.

“For people who assume it’s only a sexual thing, it’s bad to assume, because the majority of the community are minors,” said Harper. “There are a lot of kids on TikTok that will get bullied and harassed—some kids who even get death threats. I’ve seen, way back in the day, some kid get pushed to suicide that was probably thirteen, fourteen. A lot of them are minors.”

It began to seem more and more like the mistreatment of furries was really just a socially acceptable way of bullying kids who are statistically more likely to be transgender, queer or neurodivergent—who just want to find an outlet for their self-expression and creativity—with the excuse that they’re “freaks.” That because they have fursonas, there’s a justification for the harassment every furry I talked to had endured: the barking, the innuendos and the threats.

Nowadays, it’s almost impossible to get away with saying anything discriminatory that can tie back to your identity—by using anonymous, online profiles, cyberbullying is an easy way to humiliate many neurodivergent and queer kids online.

“The incentive for me was mainly just the use of anthropomorphic animals. Especially for neurodivergent people, like myself, it’s cute. The way it looks, it’s just cute,” said Tanny. Although he doesn’t own a fursuit, he has commissioned art from dozens of artists in the community. It’s a form of self-expression.

From interviewing half a dozen furries, I found out that most of the fandom consists of young kids—usually about fourteen years old. Harassment online drives some to self-hatred, and in extreme cases, even suicide. According to a 2018 study done by the University of Waikato, “suicide, anxiety and depression were significant issues within the furry community,” which was reported by a number of participants to have improved with the support of the community.

Despite the hatred many furries garner, the fandom is a bright spot in the lives of many kids.

“Just because someone says the word ‘furry’ doesn’t mean you should immediately assume, ‘Oh, this person is a freak, this person does weird stuff,’ because sometimes, it can just be innocent,” said Eliza. “Like how it was for me growing up, and still is. It’s just a fascination with fantastical anthropomorphic animals, that’s fun. It’s make-believe.”

The one thing that couldn’t get taken away from the furries I interviewed was their happy memories from the fandom—the community, the art and the sense of belonging that no amount of barking can take away.

“The best part of it, I’d say, is meeting all of the amazing and creative people within the fandom,” said Harper. “There are so many different ways of expression and different groups to fit in with. I don’t think I would be the person I am today without the amazingly supportive community.”

The furries aren’t lurking in Arizona, or hiding away on Reddit. Most of them don’t even have fursuits. They’re kids. They’re here, walking next to you on your way to class, laughing with their friends in the halls, and being a part of your world. And maybe, if we’re really as open-minded as we pretend to be, they won’t have to hide anymore.

“Mom, I finally made it in the newspaper! Are you proud?”

A brilliant mind and philanthropist, Adri enjoys classical music, regular music, rock music and all other types of music, as well as various...

Jesse Radzik • May 18, 2023 at 3:58 pm

This is brill