Praise the ‘Femcel’

Girls just want to have fun—right? Involuntary celibacy, feminism in the 21st century and defining identity via internet aesthetics

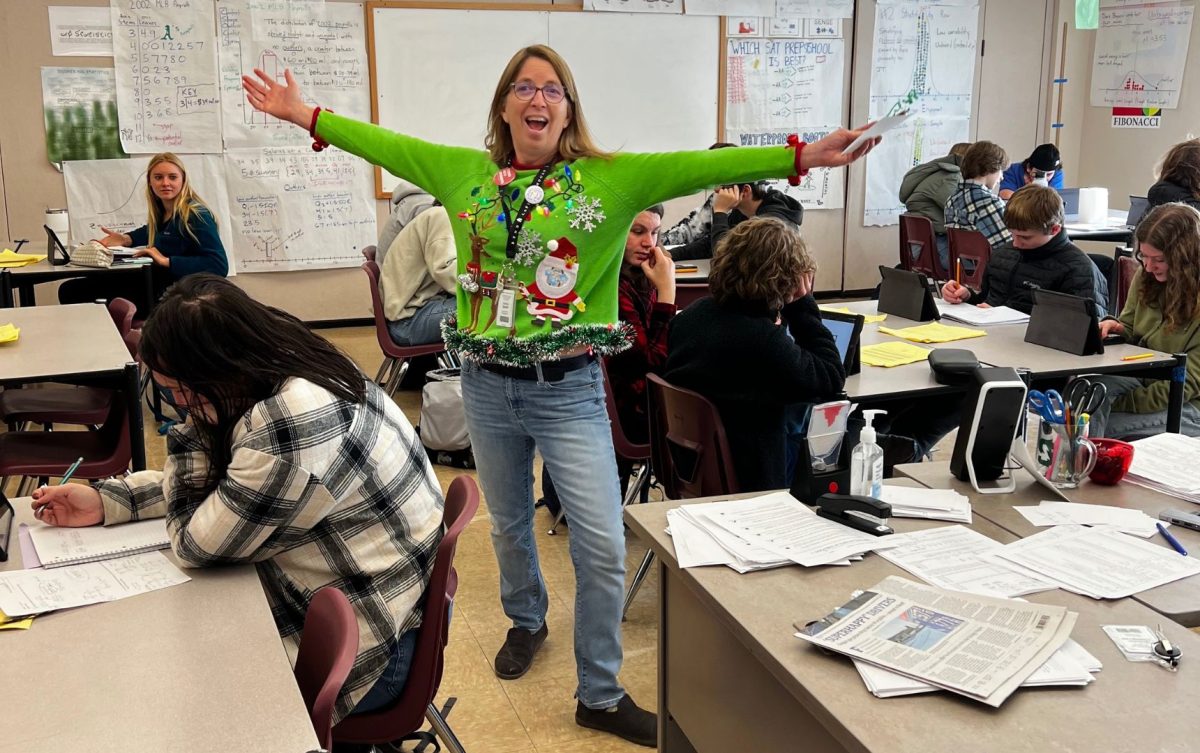

There is a girl who reveres Lux Lisbon of “The Virgin Suicides.” She wears a rosary, hailing Mother Mary even though she doesn’t believe in the Catholic Church, and craves a cigarette just for the idea of balancing a Marlboro Red between her first and second fingers. A self-assigned Patrick Bateman archetype—only with Fiona Apple’s “Tidal” playing on his walkman instead of Huey Lewis and the News—she leaves lipstick on her Diet Coke, reposts Plath poems on her Instagram story and thinks she’s a misandrist. She calls herself a “femcel.”

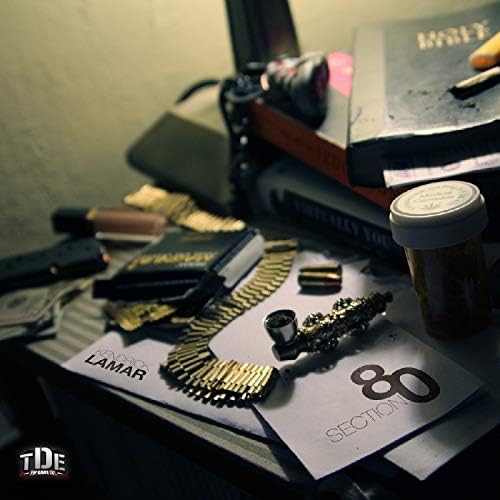

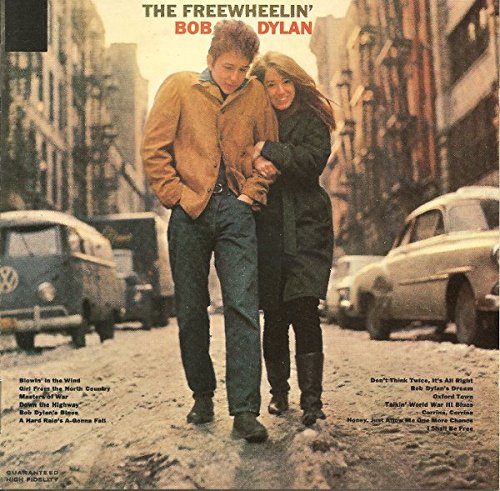

And so she is. At least an aestheticized, nearly fetishized version. Originally, “femcel” and similar “female manipulator” labels stemmed from the masculine counterparts that first came before them: incels, the Redditers collecting dust in someone’s mom’s basement, and male manipulators—the Morrissey-dedicated record store frequenters desperate for their “500 Days of Summer” encounter.

But whereas incels—a portmanteau of the term “involuntary celibate”—blame their collective inability to get laid on women themselves and the accursed current waves of feminism, the femcel movement is allegedly reclaiming female sexuality and redirecting frustrations at a greater patriarchy. Modern femcels have turned their back on an outdated Urban Dictionary definition, one in alignment with that of an incel, and are redefining the term.

“A femcel is a woman who rejects the culture of misogyny that is built into society,” said Avery Julià-Suriano, Summit junior and self-identified femcel. “She’s a woman who lives her life to her standards, and enjoys the things that she enjoys, despite the backlash that she might receive from a male-dominated society. And it’s not necessarily that she hates men, but she understands that this society is built for them and not for her, and that the only way that she might be able to fight back against that is, maybe, celibacy. Maybe it’s just acting out. Maybe it’s just being a radical, unapologetic woman. That’s femceldom to me.”

In a lot of ways, femceldom is just a new take on feminism—a more “dissociative” feminism, born in the face of recent millennial “girlboss” movements. Less “girl power” posters, more red flags. This concept of choosing celibacy by means of reclaiming femininity nearly parallels that of nunhood—only, the “God” femcels are devoting themselves to is, really, just themselves. Femcels are simply living their lives on their own terms, and that means a lot of different things for a lot of different people.

“I feel like for female manipulators, it’s like you’re yearning—I hate using ‘yearning’ to talk about them—but they desire to be saved by a man, kind of,” said Summit junior Dakota Bender. “I feel like femcels both yearn for it, but also reject it, just because of past treatment.”

Beyond a frame of mind, the femcel identity is simply an aesthetic to latch onto. Lobotomy chic, you can’t save her. This is a girl who read Ottessa Moshfegh’s “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” and found there a set of principles to live by. This is a girl who is in her “Girl Interrupted”-“Black Swan”-“Fleabag”-name another piece of media about a corrupted white girl with mental health issues et cetera-era. And none of that has anything to do with this invented incel concept of “involuntary celibacy.” Because really, femceldom is not about sex. Or inherent lack thereof, either.

“There’s also the whole, like, ‘feminine rage’ type of thing, and like recognizing yourself—seeing yourself—in these certain female characters,” said Bender. “Like ‘Gone Girl’ Amy Dunne type beat, or Pearl from ‘Pearl.” Or, [femcels’] big thing: ‘The Virgin Suicides.’”

Dedicated Spotify playlists titled the “Ultimate femcel female manipulator alpha girl playlist” or the “girlbossification of femcels” compile Lana Del Rey, Mitski and Radiohead as this pinnacled Amy Dunne femininity—that being, girlhood laced with just a bit of batshit crazy. Take Fiona Apple, for example. Self-identified “femcels” on TikTok took Apple’s music to feed into the conceptual manic-sad-girl lifestyle and to effectively confine her to the same box they are confining themselves to—ultimately leading Apple to wipe her discography from the app.

For femcels, confining one’s identity to a set of abstract ideas and key words forges a visual—more “beautiful”—sense of the suffering, brought on by a male-dominated world. Simply, rose-colored seduction in the face of destruction. But at what point does manufacturing silver linings turn into girls commodifying themselves and their mental health for the sake of society?

“I feel like I myself do that sometimes,” Bender said. “There’s a total difference between using this thing to cope, versus glamorizing it. I feel like it’s totally fine to romanticize your suffering for personal reasons, but at the same time [femcels] have made it into an aesthetic.”

Women are taught from birth to repackage themselves and their suffering into something digestible, and these “femcel” and “female manipulator” internet identities allow just that in an accessible—albeit problematic—way. By forging a visual aesthetic of an intangible identity who lives sans fear of consequence, girls create space for themselves to coexist that—otherwise—would not exist. A space to be messy and mean and okay with that.

“A lot of people don’t like labels, but sometimes it’s nice to feel like you’re in a box, and like you can identify with something and connect with other people on that,” Julià-Suriano said. “I joke all the time, like, ‘I hate men, I’m anti-man, I’m a misandrist, I’m a femcel.’ All of these things are true, but I’m not doing that because it’s ‘cool’ and glamorized and romanticized. I am this way because I have not had positive experiences in a male-dominated society with men who conform to it.”

Yes, this femcel identity has manifested mostly into a glamorization of conscious destruction. But it’s also provided a sense of sanctity for many. Girls deserve—to some extent—to be messy and to figure life out. Also, no femcel has taken on the greater incel terrorist agenda, and that is important to note.

In a lot of ways, femceldom turns into a dress-up game. By conforming to an identity pre-defined for you, here’s a streamlined path to a mock self-discovery. But as a teenage girl who’s just trying to figure out the world, there’s nothing wrong with that. That’s part of the fun of it. You don’t actually need to read Joan Didion to look like you do. You don’t actually have to light your Marlboro, so long as you pretend you do.