Know History, Know Self

The fight for a more inclusive curriculum takes center stage in Bend.

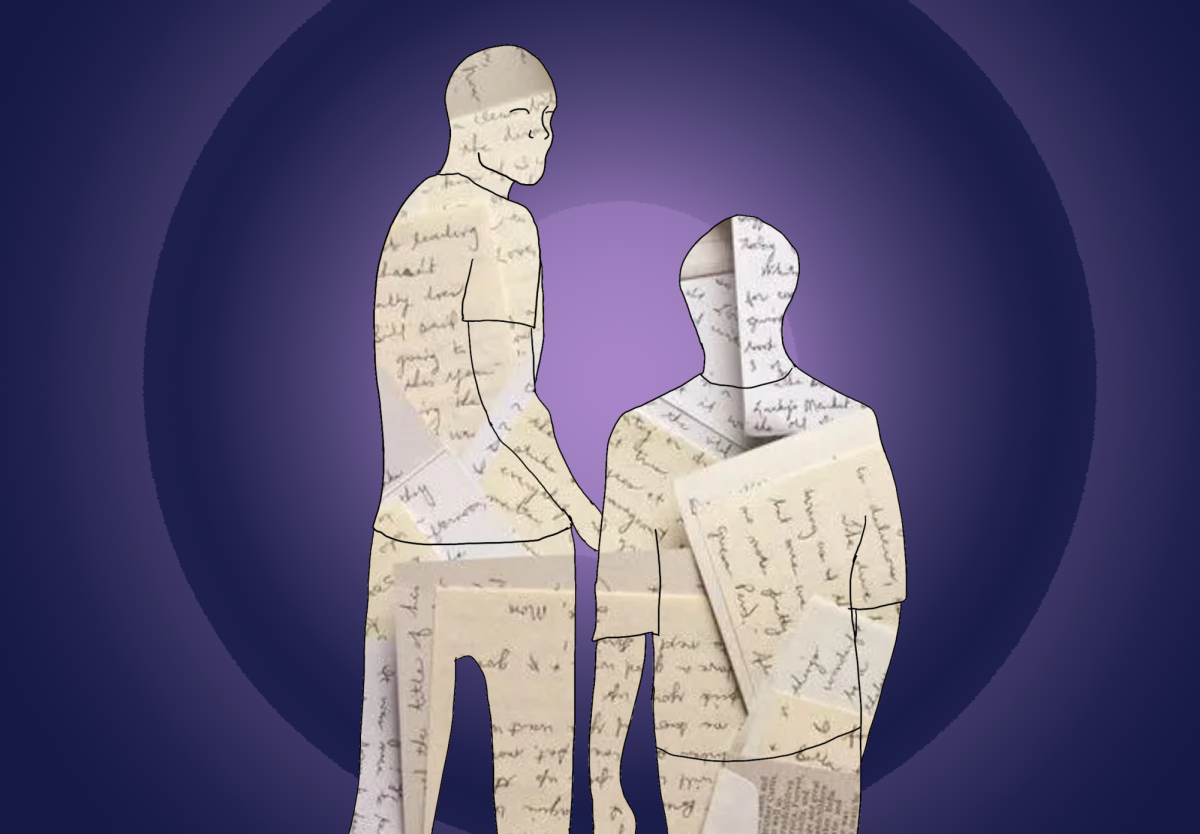

A group of Portland students were indignant. Not because of the food in the cafeteria or the length of the passing periods, but because their textbooks were missing pages. In 2015, they took it upon themselves to demand Ethnic Studies classes in their schools. Now, the fight for a more inclusive curriculum is taking center stage in Bend.

Ethnic Studies is the examination of society, particularly as it pertains to the experiences and history of ethnic and social minorities. In June 2017, House Bill 2845 was signed into law, making Oregon the first state to require Ethnic Studies for kindergarten to 12th grade students. The bill created an advisory group, comprised of 13 representatives from different commissions and communities, with a goal of producing new state standards.

Cultural identities, discrimination throughout history and systems of power are just a handful of the topics that will be required. The “2021 Social Science Standards Integrated with Ethnic Studies” can now be implemented by school districts across the state, but this curriculum will not be required until the 2026-2027 school year.

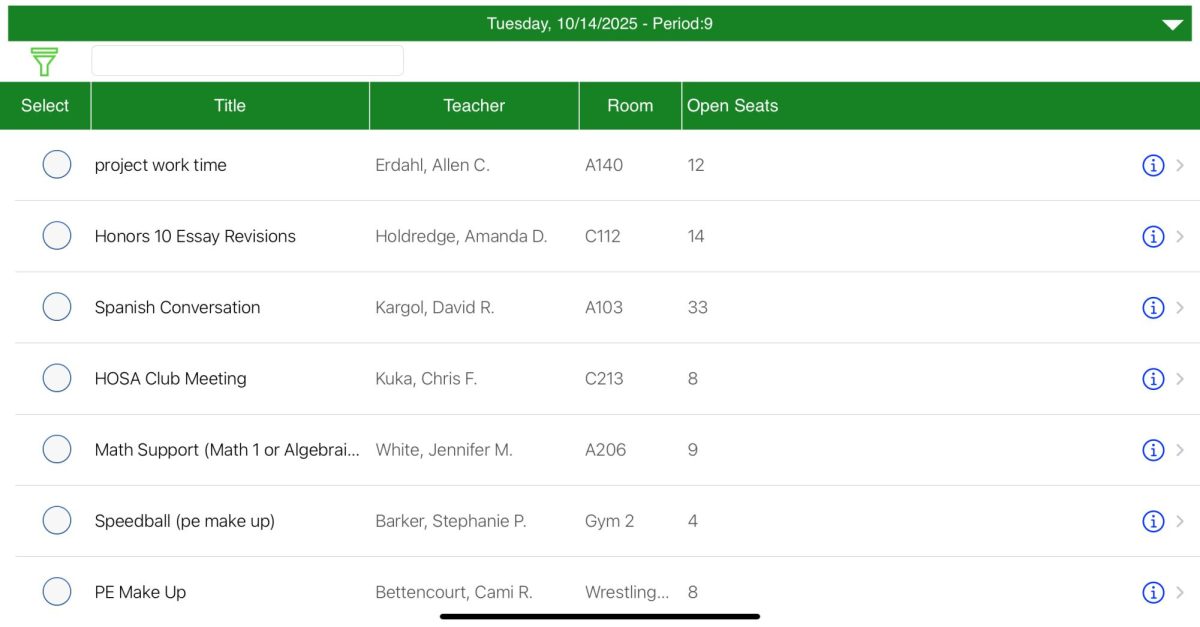

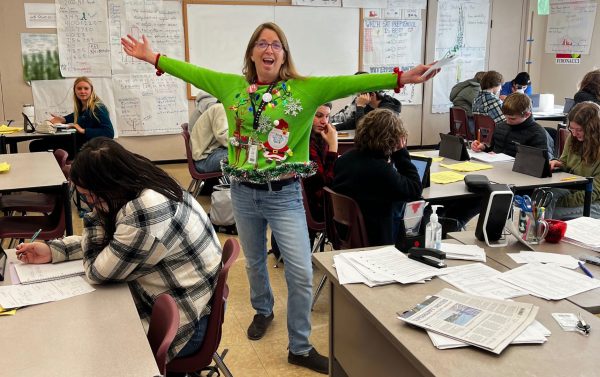

For the second year, Summit is offering an Ethnic Studies elective.

Still, not all are in favor of this change. Last year, the general election for the Bend-La Pine school board drew national attention because of conflicting views on highly politicized topics—primarily Ethnic Studies.

Maria Lopez-Dauenhauer, a candidate for zone 1 (an area which includes Summit), appeared on the Laura Ingraham Show, a particularly conservative broadcast on the Fox News Channel. In addition to national coverage, she received lots of local attention due to allegations of social media harassment.

“I am concerned about the rise of reverse-racism and identity politics that are now dominating public policies and affecting the curriculum,” said Lopez-Dauenhauer during an interview with the Bend Bulletin.

This idea isn’t new. In fact, it is strikingly similar to the reasoning that Arizona politicians used to pass a ban on Ethnic Studies in schools in 2010.

When speaking with Carrie McPherson Douglass, a current member of the Bend-La Pine school board, she said that pushback in reaction to Ethnic Studies curriculum results from confusion.

“People are just responding to politicians’ encouragement,” said Douglass.

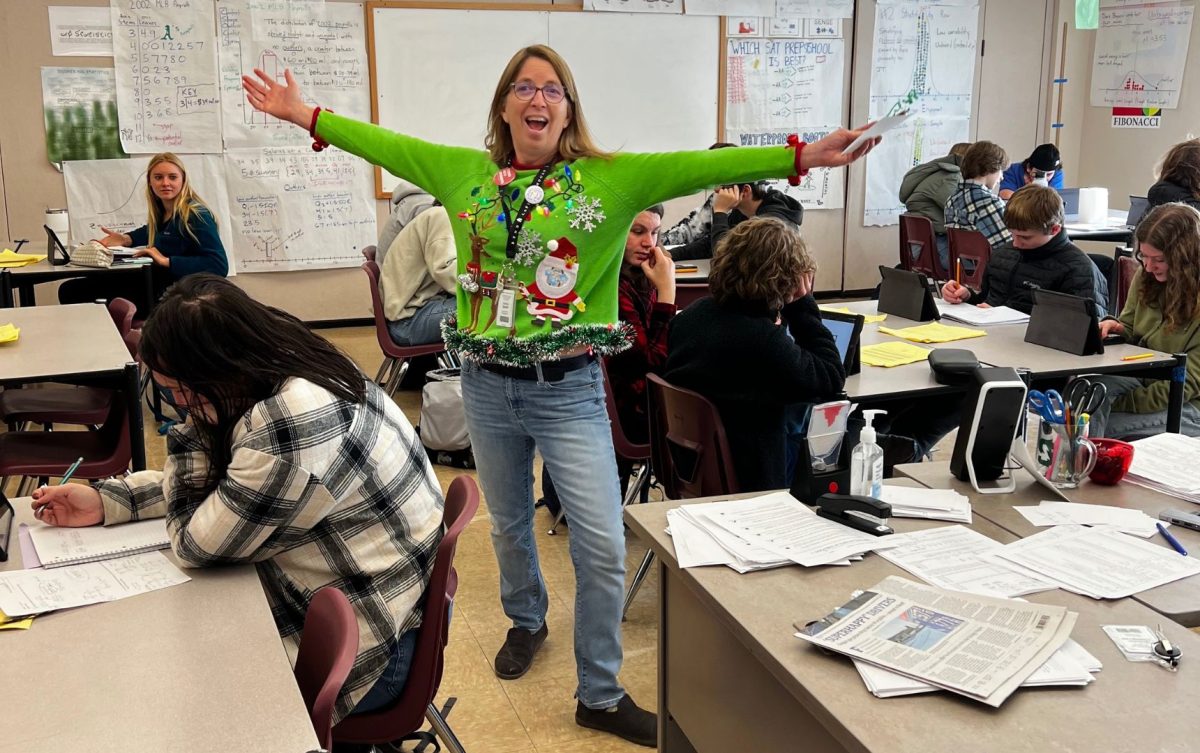

Similarly, Marni Spitz, an Ethnic Studies teacher at Summit, believes that “[people who oppose Ethnic Studies] make the narrative about how it affects people in power.” Many politicians and concerned parents argue that Critical Race Theory—the idea that race is a social construct—teaches children to feel guilty about their “whiteness” while putting white people at a “disadvantage.” Instead, Spitz believes that Ethnic Studies is about empowering underrepresented narratives, not dismissing dominant ones.

Like Spitz, many people view these classes as liberating.

“Students learn better when all views and perspectives are included,” Douglass said.

A Stanford study assigned a group of students with a GPA of 2.0 or lower to an Ethnic Studies class during their freshman year of high school. 90% of the students graduated within five years and were 15% more likely to enroll in college, compared to a graduation rate of 75% among the students that did not take this class.

According to Douglass, the Bend-La Pine school district has implemented many of the state standards because of their belief that Ethnic Studies is immensely beneficial for students.

But it is important to note that the Stanford study took place at public schools in San Francisco, where 90% of the students assigned to an Ethnic Studies class were Hispanic, Asian or Black. So are these classes still important in Bend, a predominantly white town in Central Oregon?

Spitz says yes. Although Summit is relatively “racially homogenous,” our community is still diverse in many other ways. And according to the results from one teacher’s survey last year, the class made students feel more comfortable talking about controversial issues and more informed about current events, in addition to opening their minds.

In more racially diverse communities, Spitz believes that the need for Ethnic Studies may be more urgent and reflected in the community. But she agrees that Bend is making huge strides.

“It has to start with what we teach,” Spitz said. Changing the future starts with education now.

Usually found outside, the wild Dailey can be spotted frolicking in the woods or on top of a mountain. She enjoys visiting unknown places whether that’s traveling to Myanmar or backpacking into the middle-of-nowhere...